How to achieve a region-wide free trade agreement?

A region-wide free-trade agreement (FTA) is considered to be one way of solving the Asian “noodle bowl” syndrome, but there are various views on how to achieve it.

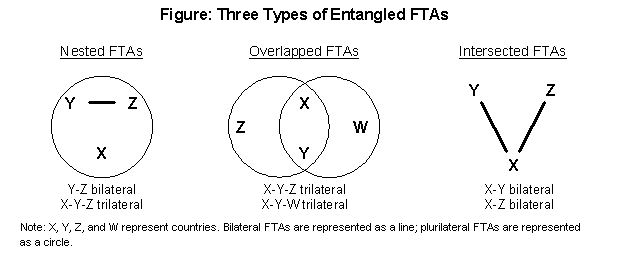

It is critically important to distinguish between the three main types of “entangled” FTAs.

1. In “nested” FTAs the members of a small agreement are a subset of the members of a larger agreement. Nested FTAs simply offer more options to traders, enabling them to choose the most beneficial rule.

2. In “intersected” FTAs, one country has different agreements with different rules with different partners.

3. “Overlapped” FTAs have features of both nested and intersected FTAs.

We need to be very clear about which problem needs to be solved: multiple options for one trade in the case of nested FTAs, or different rules for different trade partners in the case of intersected FTAs.

Several studies point out there are two possible approaches toward a region-wide FTA: consolidation and expansion.

The consolidation approach has four steps: (i) networking the region through bilateral FTAs between major powers, (ii) harmonizing rules under each FTA, (iii) merging several FTAs into a single region-wide FTA, and (iv) suspending old bilateral FTAs.

The expansion approach has two main steps: (i) establishing a plurilateral FTA with accession clauses and (ii) accepting new members.

Ultimately, the consolidation approach solves the noodle bowl problem by replacing old bilaterals with a single region-wide FTA. In contrast, the expansion approach attempts to create a situation where there is no need to use bilaterals by establishing a deep region-wide agreement.

If policymakers in the region opt to consolidate various ASEAN+1 FTAs, they will need to identify which ones should be consolidated. If they fail to manage the process, there is a risk of having two region-wide FTAs in Asia: a small ASEAN+1 FTA and a large ASEAN+β FTA, which would further complicate the situation.

Moreover, proponents of the consolidation approach need to understand that nested FTAs do not seem to create actual problems for traders. For example, trade between New Zealand and Singapore is governed by several FTAs, including a Singapore–New Zealand FTA, the TPP, and Australia-New Zealand-ASEAN Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA). Yet those do not seem to have caused serious confusion.

Furthermore, if consolidation entails the suspension of old bilateral FTAs, this would be unfavorable to traders – the consolidated agreement tends to be more restrictive than old bilaterals. That is why Singapore and New Zealand decided not to suspend the bilateral FTA even after the launch of the TPP.

The TPP, which started with an agreement signed by Brunei Darussalam, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore in 2006, has a chance to form the basis of a future region-wide FTA. Accession to the TPP is open to any country. In fact, after the US decided not to pursue bilateral FTAs with Asian countries and instead allocated resources to negotiate the TPP in 2009, the queue of Asian countries’ proposing bilateral FTAs with the US was replaced by a queue of Asian countries’ participating in TPP negotiations.

Four issues should be carefully considered by TPP members if the agreement is to evolve into a true region-wide FTA.

First, the TPP should not be a mere consolidation of existing bilateral FTAs between Asia-Pacific countries. In other words, the TPP negotiations should not be constrained by existing bilateral FTAs between potential TPP members. For example, it has been reported that the US has asked Australia not to re-open the sugar issue in the TPP talks since sugar is already excluded from the Australia–US FTA. Equal treatment between “haves” and “have nots” is needed.

Second, the TPP should have clear accession criteria. Latecomers should not be required to concede more than earlier members. Because there is a possibility that earlier members might utilize a veto threat if given such power, accession should be on a majority basis. If a single country objects to the accession of a new member, the provisions of the agreement should not apply to the trade relationship between that country and the acceding country.

Third, whether the same accession criteria should be used for developing country applicants should be openly discussed. Ideally, TPP should be gracious in accepting applications from developing countries even if they cannot offer a comparable level of concessions.

Fourth, the name itself may preclude otherwise potential members from joining TPP. While the TPP does not set geographical conditions for applicants, a country that does not regard itself as a Pacific entity, like India, may simply choose not to join.