Asia’s FTAs as living agreements: Creating new opportunities amid global trade uncertainties

Trade tensions among the world’s major economies have dominated news headlines recently, casting a shadow of uncertainty on international trade and endangering the prospect of sustained global economic growth. A recent series of unorthodox and unprecedented trade policy moves have been featured in headlines, such as the US pull-out from the TPP and the renegotiations of NAFTA and KORUS, a free trade agreement (FTA) highly recognized for its “gold standard” provisions when it came into force in 2012.

Meanwhile, a relatively unnoticed development is emerging that could shape the future of Asia’s FTA landscape—the upgrading of existing Asian FTAs or FTAs involving at least one Asian economy. As this evolves, pockets of opportunities that can help achieve greater trade liberalization begin to dot the global trade picture, even as more countries resort to inward-looking policies.

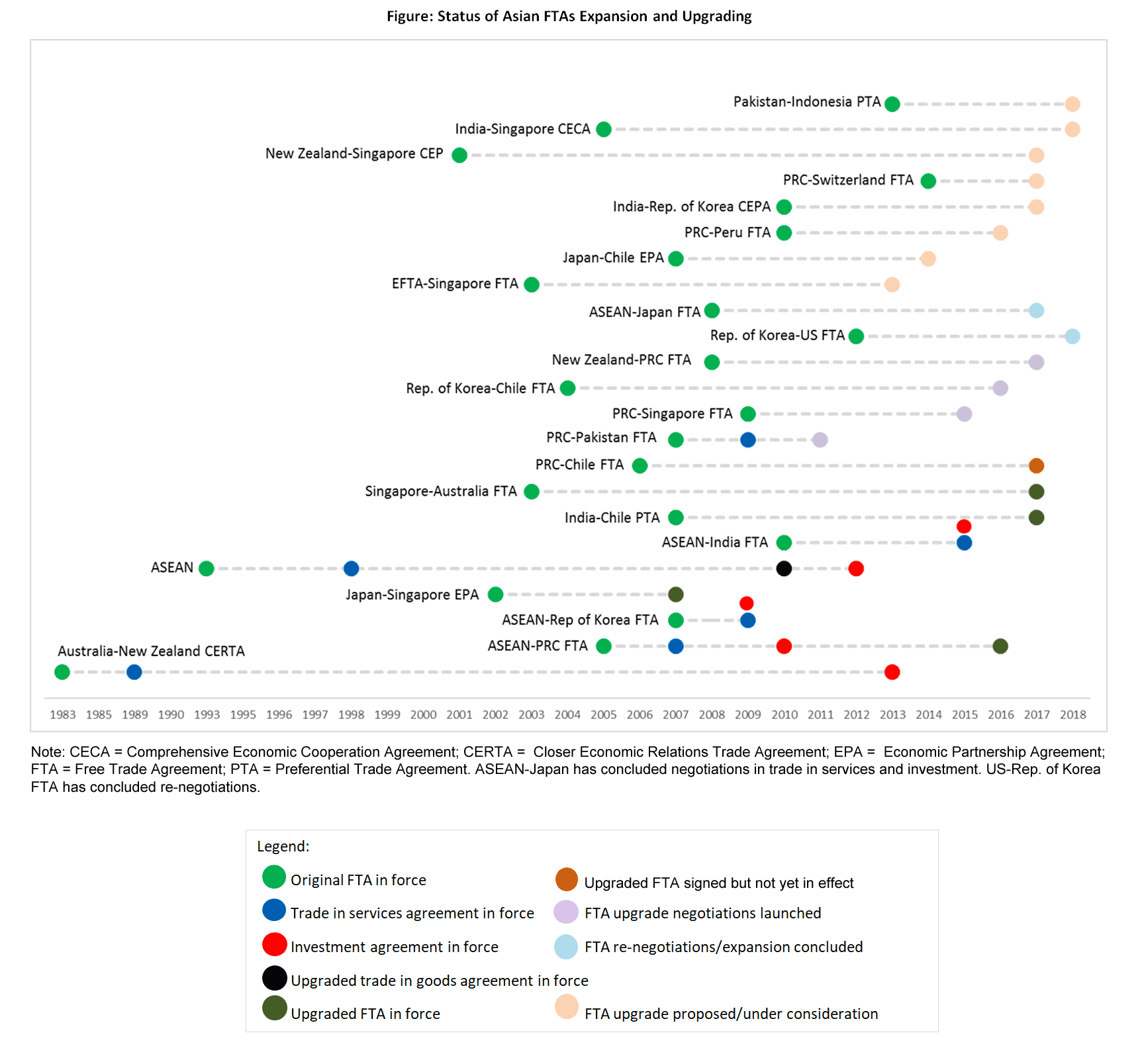

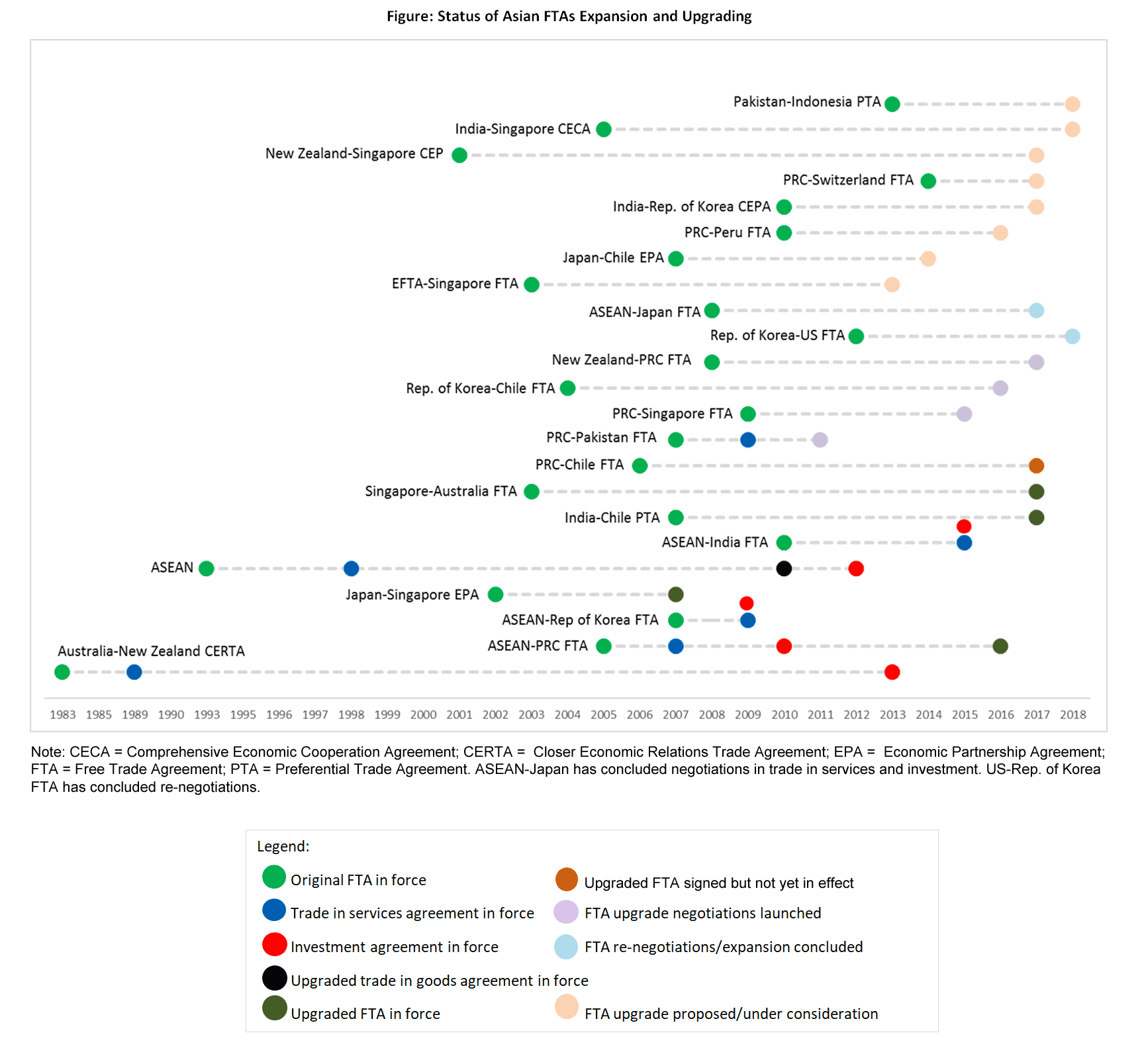

The sudden increase in the number of Asian FTAs going through various stages of upgrading is a new phenomenon, intensifying only in the last two years (Figure). The staggered improvement of trade agreements towards greater liberalization is not a new strategy for Asian FTAs. In the past, we have seen the progression of several Asian FTAs, either in terms of expansion, such as the conclusion of an agreement to liberalize services trade following an agreement in trade in goods, or upgrading to deepen existing liberalization commitments and include “behind-the-border” issues such as investment, trade facilitation, competition, and government procurement.

One example is the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) which was established in 1993 to bring down import tariffs and enhance trade among ASEAN members, and expanded with the coming into force of the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services in 1998. The trade bloc deepened its tariff liberalization commitments with the enforcement of the ASEAN Trade in Goods in 2010 and resulted to the bulk of intra-ASEAN trade being now duty-free. AFTA further upgraded with the effectivity of the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement in 2012.

FTAs as living agreements

In a world of rapidly changing economic realities, FTAs are not supposed to be written in stone. Several FTAs are considered living agreements with a so-called ‘built-in agenda’ to keep them attuned to the demands of the current economic environment. This built-in agenda includes provisions for review, joint committees and working groups, which allow FTA partners to explore ways to build on results and to maximize FTA benefits. All FTAs currently undergoing modification include at least one of these provisions.

Upgraded FTA commitments provide greater market access underpinned by new rules creating more certainty for exporters of goods, services and investment. The latest upgraded FTA, the Singapore-Australia FTA (SAFTA), which took effect on 31 December 2017, makes for a good illustration. The upgraded SAFTA elevates economic relations between Singapore and Australia to the next level.

Singapore companies can now bid for procurement contracts from Australia’s federal government and its eight states and territories. While Australian companies are already winning high-value contracts with the Singapore government, the expanded SAFTA locks in these gains in sectors such as road transport, construction and engineering. Singapore investors no longer need to seek approval from Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board for investments with maximum value of $1.12 billion in “non-sensitive” sectors. Moreover, it has increased flexibility of rules of origin, making it easier for exports to qualify for tariff-free treatments, reduced regulatory barriers to better facilitate trade in goods such as wine, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical products, and improved mobility and duration of stay of business people.

The upsurge in FTA upgrading and expansion is largely triggered by the built-in agenda provisions in FTAs. For instance, the original SAFTA includes a provision for review and the upgraded version reflects the outcomes of one of the reviews conducted. Meanwhile, the ASEAN-Japan FTA includes a provision to negotiate an agreement in trade in services and investment. For some FTAs, however, external factors create the impetus for upgrading.

New Zealand and PRC has agreed to upgrade the nearly decade-old FTA (NZ-PRC FTA) in November 2016, following the entry into force of the PRC-Australia FTA (ChAFTA) in December 2015. Australia and New Zealand are major exporters of dairy products and the PRC is their biggest importer. ChAFTA gives market access to Australian dairy producers that place them in a much more competitive footing with New Zealand’s export-driven dairy industry. Although the NZ-PRC FTA includes a Most Favored Nation clause, which ensures that neither nation is disadvantaged by better terms struck in future trade deals, the upgrade of NZ-PRC FTA presents an opportunity for New Zealand to lock-in the better terms that ChAFTA may possibly have.

The existing NZ-PRC FTA has already sealed substantial tariff elimination. This gives the upgrade negotiations more room to advance trade liberalization beyond tariff, particularly in the area of non-tariff measures such as technical barriers to trade (TBT), rules of origins, and trade facilitation. Upgrading efforts also cover deep integration issues such as services trade, competition policy, e-commerce, and government procurement.

A new frontier in trade openness

The first decade of the 21st century saw an exponential rise in the number of Asian FTAs — a trade policy tool rarely used until the 1990s. The early players in Asia’s FTA field — the drivers of FTA growth in the 2000’s — are now leading the efforts to upgrade existing FTAs. The rise of Asia’s FTA upgrading is accompanied by stagnating FTA growth in Asia with only an average of seven FTAs signed and/or in force in the last two years, way below its double-digit average in the 2000’s until 2015. In effect, although trade openness in terms of new FTAs is nearing a plateau, upgrading Asia’s FTAs to bring down remaining trade impediments advances liberalization to new heights.

The deepening of existing FTAs faces a new frontier in trade liberalization now that tariffs are generally low. SAFTA and NZ-PRC FTA are examples of how upgrading efforts of the early players in Asia’s FTA field went beyond tariff concessions and have focused on reducing regulatory barriers to improve trade in goods alongside achieving greater liberalization of investment, services trade, and even government procurement.

Given Asia’s close links to global value chains, it is to the region’s advantage to promote a liberal trade regime. In a world of rising trade tensions, stalled FTA growth, and already low tariffs, advancing trade openness faces new challenges. Upgrading Asia’s FTAs with an eye to liberalizing behind-the-border barriers to trade and investment and harmonizing domestic trade rules to improve efficiency of international production will inject new impetus to trade openness.

Figure: Status of Asian FTAs Expansion and Upgrading

(click to enlarge)

Trade tensions among the world’s major economies have dominated news headlines recently, casting a shadow of uncertainty on international trade and endangering the prospect of sustained global economic growth. A recent series of unorthodox and unprecedented trade policy moves have been featured in headlines, such as the US pull-out from the TPP and the renegotiations of NAFTA and KORUS, a free trade agreement (FTA) highly recognized for its “gold standard” provisions when it came into force in 2012.

Meanwhile, a relatively unnoticed development is emerging that could shape the future of Asia’s FTA landscape—the upgrading of existing Asian FTAs or FTAs involving at least one Asian economy. As this evolves, pockets of opportunities that can help achieve greater trade liberalization begin to dot the global trade picture, even as more countries resort to inward-looking policies.

The sudden increase in the number of Asian FTAs going through various stages of upgrading is a new phenomenon, intensifying only in the last two years (Figure). The staggered improvement of trade agreements towards greater liberalization is not a new strategy for Asian FTAs. In the past, we have seen the progression of several Asian FTAs, either in terms of expansion, such as the conclusion of an agreement to liberalize services trade following an agreement in trade in goods, or upgrading to deepen existing liberalization commitments and include “behind-the-border” issues such as investment, trade facilitation, competition, and government procurement. Â

One example is the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) which  was established in 1993 to bring down import tariffs and enhance trade among ASEAN members, and expanded with the coming into force of the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services in 1998. The trade bloc deepened its tariff liberalization commitments with the enforcement of the ASEAN Trade in Goods in 2010 and resulted to the bulk of intra-ASEAN trade being now duty-free. AFTA further upgraded with the effectivity of the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement in 2012.

FTAs as living agreements

In a world of rapidly changing economic realities, FTAs are not supposed to be written in stone. Several FTAs are considered living agreements with a so-called ‘built-in agenda’ to keep them attuned to the demands of the current economic environment.  This built-in agenda includes provisions for review, joint committees and working groups, which allow FTA partners to explore ways to build on results and to maximize FTA benefits. All FTAs currently undergoing modification include at least one of these provisions.

Upgraded FTA commitments provide greater market access underpinned by new rules creating more certainty for exporters of goods, services and investment. The latest upgraded FTA, the Singapore-Australia FTA (SAFTA), which took effect on 31 December 2017, makes for a good illustration. The upgraded SAFTA elevates economic relations between Singapore and Australia to the next level.

Singapore companies can now bid for procurement contracts from Australia’s federal government and its eight states and territories. While Australian companies are already winning high-value contracts with the Singapore government, the expanded SAFTA locks in these gains in sectors such as road transport, construction and engineering. Singapore investors no longer need to seek approval from Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board for investments with maximum value of $1.12 billion in “non-sensitive” sectors. Moreover, it has increased flexibility of rules of origin, making it easier for exports to qualify for tariff-free treatments, reduced regulatory barriers to better facilitate trade in goods such as wine, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical products, and improved mobility and duration of stay of business people.

The upsurge in FTA upgrading and expansion is largely triggered by the built-in agenda provisions in FTAs. For instance, the original SAFTA includes a provision for review and the upgraded version reflects the outcomes of one of the reviews conducted. Meanwhile, the ASEAN-Japan FTA includes a provision to negotiate an agreement in trade in services and investment. For some FTAs, however, external factors create the impetus for upgrading.

New Zealand and PRC has agreed to upgrade the nearly decade-old FTA (NZ-PRC FTA) in November 2016, following the entry into force of the PRC-Australia FTA (ChAFTA) in December 2015. Australia and New Zealand are major exporters of dairy products and the PRC is their biggest importer. ChAFTA gives market access to Australian dairy producers that place them in a much more competitive footing with New Zealand’s export-driven dairy industry. Although the NZ-PRC FTA includes a Most Favored Nation clause, which ensures that neither nation is disadvantaged by better terms struck in future trade deals, the upgrade of NZ-PRC FTA presents an opportunity for New Zealand to lock-in the better terms that ChAFTA may possibly have.

The existing NZ-PRC FTA has already sealed substantial tariff elimination. This gives the upgrade negotiations more room to advance trade liberalization beyond tariff, particularly in the area of non-tariff measures such as technical barriers to trade (TBT), rules of origins, and trade facilitation. Upgrading efforts also cover deep integration issues such as services trade, competition policy, e-commerce, and government procurement.

A new frontier in trade openness

The first decade of the 21st century saw an exponential rise in the number of Asian FTAs — a trade policy tool rarely used until the 1990s. The early players in Asia’s FTA field — the drivers of FTA growth in the 2000’s — are now leading the efforts to upgrade existing FTAs. The rise of Asia’s FTA upgrading is accompanied by stagnating FTA growth in Asia with only an average of seven FTAs signed and/or in force in the last two years, way below its double-digit average in the 2000’s until 2015. In effect, although trade openness in terms of new FTAs is nearing a plateau, upgrading Asia’s FTAs to bring down remaining trade impediments advances liberalization to new heights.

The deepening of existing FTAs faces a new frontier in trade liberalization now that tariffs are generally low. SAFTA and NZ-PRC FTA are examples of how upgrading efforts of the early players in Asia’s FTA field went beyond tariff concessions and have focused on reducing regulatory barriers to improve trade in goods alongside achieving greater liberalization of investment, services trade, and even government procurement.

Given Asia’s close links to global value chains, it is to the region’s advantage to promote a liberal trade regime. In a world of rising trade tensions, stalled FTA growth, and already low tariffs, advancing trade openness faces new challenges. Upgrading Asia’s FTAs with an eye to liberalizing behind-the-border barriers to trade and investment and harmonizing domestic trade rules to improve efficiency of international production will inject new impetus to trade openness.

Figure: Status of Asian FTAs Expansion and Upgrading

(click to enlarge)

*

*

Dorothea Ramizo is an economic analyst at the Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department of the Asian Development Bank

Dorothea Ramizo is an economic analyst at the Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department of the Asian Development Bank