Reshore or Diversify? How to Reorganize the World’s Fragile Supply Chains

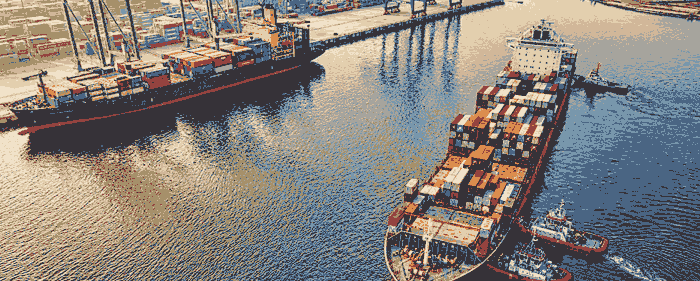

Trade conflicts, the pandemic, and geopolitical tensions have all had an impact on global supply chains. It’s time to rethink how these crucial production links are set up and how they can be made more resilient.

One key lesson of the pandemic and subsequent supply and demand mismatches is that global supply chains are fragile. They have been struggling amidst uneven economic recovery and trade conflict between global heavyweights, and are suffering geopolitical risks that are critically weighing on food and energy supplies.

Businesses, particularly in manufacturing, are finding it difficult to source inputs and engage seamless, multistep logistics and delivery management systems across borders. At national level, this has resulted in shortages in key medical products and equipment during the health crisis, shipping and transportation costs going through the roof, and security concerns about the heavy reliance of critical goods and commodities from countries that could turn less supportive or even antagonistic in a volatile geopolitical environment.

The time is right to rejigger global supply chains. One school of thought is to diversify those further away from places prone to disruptions due to economic, health, climate change and geopolitical issues. The other is bringing the production capacity back to the home country (onshoring) or to countries nearby (nearshoring). The benefits of diversification transcend sheer cost minimization. They also involve gains from risk mitigation and securing back-up sourcing plans in case of a threat to existing supply chain security.

Nearshoring utilizes geographical, or even cultural and political proximity of neighboring countries for upstream or downstream segments of supply chains. Onshoring builds production capacity of goods at home, often intending to cover the end-to-end business streams of designing, sourcing, manufacturing, marketing, distribution, sales and post sales services.

Regional trade blocs or agreements such as the European Union, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) support nearshoring. The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) is another example, although it can fall under the category of ‘friendshoring’ as touted by some people, where the scope of “friend” goes beyond the geographical boundary.

The time is right to rejigger global supply chains.

Although concerns are growing about potential fragmentation of global supply chains based on a few trading blocs among allies, the future of global supply chains may not follow one common path, and will unfold differently depending upon countries’ priorities and sectoral characteristics. It is also worth noting that a government’s industrial policy can do only so much and the ultimate reconfiguration of supply chains is hugely dependent upon how businesses take supply chain risks on board and how they respond to incentives provided governments.

While supply chain risk management seems to have become part of operational decisions in many C suites, cost efficiency and gains from specialization and trade are something that business cannot entirely forgo. In this sense, reshoring or onshoring versus further diversification of supply chains may not be viewed as an either/or choice, but as strategies to be pursed in parallel.

Some sectors will rely more on reshoring while others will focus on further diversification, subject to supply chain vulnerabilities and the expected gains from repositioning of management strategies.

In rejiggering supply chains, governments should consider:

First, reshoring needs to be pursued in a selective and efficient way. No matter how ambitious a country might be, reshoring across broad industries is neither possible nor desirable given additional cost implications and inefficiencies involved in bringing back home part of supply chains.

Although we hear a lot about the need to rebuild production capacity of semiconductors in the US and EU, with their heavy reliance upon East Asia for manufacturing (foundry), this doesn’t mean they have forgone the sector entirely over time. They have rather become specialized in high value-added, upstream segment of the chips supply chain such as Electric Design Automation (EDA) and Discrete, Analogue, and Optoelectronics and sensors (DAO), relegating simpler manufacturing processes largely to Asian economies.

By encompassing the manufacturing segment, reshoring will certainly enhance supply chain security for this critical “new oil” of the economy, yet with additional cost implications at least for the short-term. This is where technological advances can play a role and the level of technological sophistication vis-à-vis traditional foreign peers will characterize the efficiency of such reshoring strategies.

Second, reshoring strategy may not solely target outsourced production capacities of domestic companies. Attracting foreign investment could also be a part of strategy to cope with short-term domestic constraints in human and physical capital mobilization. Domestically incorporated foreign invested enterprises will make no less contribution to expanding production capacity and job creation than local companies, let alone the expected technology spillovers.

Third, diversification motives may not be based solely on cost efficiency, but should consider risk management perspectives. For this, the offshoring of production to multiple sites with lower correlation of various supply chain disruption risks will help. This also corroborates the rationale that free trade agreements should be explored not only with geographical neighbors but with trade partners further afield to expand the scope for such opportunities.

Lastly, while government incentives to rejigger supply chains could be effective in jumpstarting businesses’ motivation to reshore or diversify, this may not ensure the long-term sustainability of such approaches, given that subsides tend to ameliorate fixed costs for investment or tax payment, not operational costs.

Incentives for export competitiveness could also have some implications on WTO compliance and stoke retaliatory reactions from trading partners. So, the success of such strategies will hinge on how a good eco-system could be nurtured to facilitate a virtuous cycle of outputs from newly expanded production or sourcing capacity being linked to robust demand base domestically and abroad.

Legitimate economic rationale and political motives for rejiggering supply chains may not always ensure its success unless pursued with strategic thinking and practical implementation plans, which also need to be well aligned with business incentives. Rhetoric is one thing, but implementation is another. Only those which can wisely strategize its implementation will be able to reap the benefits.

Original article was published at the Asian Development Blog and duplicated here with permission from the author. *