Why bilateral trade between the PRC and India matters

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) and India are estimated to become the world’s largest economies by 2050. This has many implications for the global economy, as well as for Asia. In 2011, the PRC and India accounted for about a fifth of global GDP. By 2040, this proportion is expected to increase to 50%. A United Overseas Bank (UOB) report projects both countries’ trade will grow quickest with theirAsian partners, which will double the Asian trade share in the world economy by 2020. The PRC and India’s rapidly growing exports to countries outside of the Asia-Pacific has resulted in increased demand for inputs from within the region. In this blog, we ask what steps policy makers might take in order to leverage on this growing trade?

Trade on the Rise

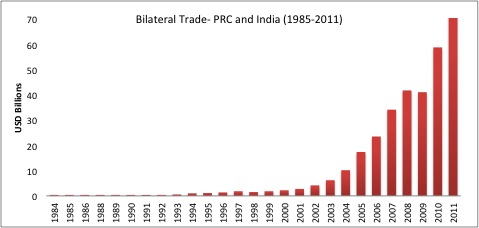

Bilateral trade between the PRC and India has grown from $2 billion to $34 billion between 1997 and 2007, hitting $70 billion in 2011, and $100 billion projected for 2015. (See Figure 1). with the change in their trade relations from non-existence, to the PRC becoming India’s largest trading partner has caused some tension over the years. With rising incomes in both the PRC and India, and a growing middle class, the opportunity cost of restricting trade between them because of political or diplomatic tensions increases considerably.

Figure 1: Growth in the volume of trade between the PRC and India.

Source: UN COMTRADE Database

The growing global presence of PRC and India, and their growing bilateral trade has attracted much attention, specifically with respect to the implications of changing patterns of trade. An assessment shows that the composition of Indian exports to the PRC has not changed significantly.. India’s exports are concentrated around primary products Between 2011 and 2012, raw materials and intermediate products (such as copper, cotton, ores, iron and steel) made up more than 90 percent of India’s exports to the PRC. Indian imports from the PRC mostly consist of high-end manufacturing and high-tech goods (such as machinery, mineral fuels, and oils) (See Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1: India’s top five imports from the PRC (2005-2012)

| 2011-2012 | 2005-2006 |

| Electrical Machinery and Equipment and parts | Electrical Machinery and Equipment and parts |

| Nuclear Reactors, Boilers, Machinery, etc. | Nuclear Reactors, Boilers, Machinery, etc. |

| Project goods, some special uses | Organic Chemicals |

| Organic Chemicals | Mineral Fuels, oil and products of their distillation |

| Fertilizers | Silk |

Source: Export-import Data Bank, Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India

Table 2: India’s top five exports to the PRC (2005-2012)

| 2011-2012 | 2005-2006 |

| Ores, Slag, and Ash | Ores, Slag, and Ash |

| Cotton | Cotton |

| Copper | Organic Chemicals |

| Mineral Fuels, oil and products of their distillation | Iron and Steel |

| Organic Chemicals | Inorganic Chemicals, precious metals, RER |

Source: Export-import Data Bank, Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India

The bilateral trade deficit that has arisen from India’s pattern of exporting low skill, low value-added products, and importing high skill, high value-added products, has strained relations between the countries. In 2011-2012, there was a trade deficit of almost $40 billion, which is twice the value of India’s exports to PRC.

Existing trade barriers are another source of tension and limit the expansion of trade in mutually beneficial areas. On the PRC side, non-tariff barriers—specifically those affecting IT services and pharmaceuticals—limit some of India’s most competitive exports. On the Indian side, the trade regime imposes the highest (of any WTO country) anti-dumping duties on the PRC, and argues that its goods continue to be artificially priced. The PRC has characterized India’s regulations on sourcing power and telecom equipment as “discriminatory”.

Moving Forward

Given the facts we have presented about bilateral trade between the PRC and India, we can recommend several policy issues that deserve attention by policymakers.

- Efforts towards a PRC-India Free Trade Agreement should continue. This process was begin in 2011 and can serve to lock in growing collaboration and cooperation between the two countries.

- Greater cooperation towards elimination of trade barriers is needed. While the last Strategic Economic Dialogue of 2012 recognized the need for trade facilitation, practical changes in market access have not been forthcoming. Services trade remains an important issue, particularly pharmaceutical and IT services.

- India must continue efforts to diversify its trade basket to address the growing trade imbalance. The PRC has already instituted policies to encourage businesses to import from India, but in the absence of Indian support for its exporters, this will have only limited impact.

- Lastly, greater focus is needed on compiling and publicizing data on bilateral trade between both economies. Differences in official data and that available from international databases such as UN Comtrade should be reconciled to enable more evidence-based policy analysis.

While both countries have come far in their economic and bilateral relations, there is still considerable scope to increase bilateral trade, and trade cooperation between them.