Why the "end of cheap China*" may be good

Rising wages in the People's Republic of China (PRC) have sparked off concerns the world over. For one, PRC-based firms will have to contend with shrinking profit margins—unless they pass on the cost to consumers or produce somewhere else cheaper. Other countries, however, may not be easy alternatives for some industries, as many are not able to match PRC's sophisticated supply networks, large pool of skilled labor, and reliable infrastructure.

Inevitably, consumers around the globe will face higher prices for many goods—from branded shoes to high-tech gizmos. And the PRC will have to deal with the threat of multinational companies (MNCs) moving out in search of cheaper pastures.

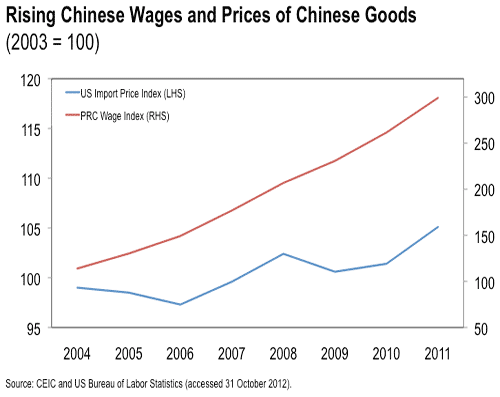

Indeed, the impending "end of cheap made in China" (see figure) has triggered much apprehension. But it also offers timely opportunities for transformation, revolution, and conversion to those able and willing to seize such opportunities.

The Chinese Transformation. The abundance of labor in the PRC has propelled the country to become the "world's factory", churning out bargain priced goods for decades. With rising Chinese wages and shortages in labor supply, however, the PRC will have to move into higher value-added manufacturing and into new industries, and to boost domestic consumption.

Moving into new industries implies expanding the services sector beyond the manufacturing sector. Moving up the value chain means that the PRC must shift from exporting cheap, labor-intensive manufactures to high-tech goods.

The PRC has been touted as the top exporter of high-tech goods. But PRC's high-tech exports are actually "assembled high-tech" exports, as the country is positioned at the final stage of the ICT production chain. To move up the value-chain, it therefore needs to be more innovative and better harness the know-how of foreign-invested firms.

Still, rising wages have their pluses. They lift domestic spending and shield the country from weak global demand. In fact, higher wages are expected to unleash a huge wave of "middle class" spending that will rival that of the U.S. by 2020.

In short, the "end of cheap China" is gradually fueling the Chinese transformation—the rebalancing toward domestic demand and a diversification of trade in the PRC. It is nudging the PRC to evolve from being a cheap manufacturing hub that is dependent on exports for economic growth toward a service-oriented and domestically driven economy.

MNC Revolution. For MNCs, the "end of cheap China" means embracing a novel way of doing business in order to survive. As Chinese wages rise rapidly, the need to better serve the large customer base in the advanced markets and to speed up the delivery of custom designs and fast-moving fashionable products means it is no longer economically viable to produce in the PRC alone and to ship the products back to the home markets. In response, MNCs are adopting the "China-plus one (or more)" strategy where they keep a factory in the PRC to cater to the huge Chinese market, while positioning other factories closer to other home markets.

This creates fantastic growth opportunity for other developing countries to share the export pie with the PRC. Foxconn Technology Group, maker of 40% of electronic gadgets in the world, has moved from coastal to inland PRC and is shifting some of its capacities to Southeast Asian countries and Mexico. Intel, a US chipmaker, has opened a factory in Viet Nam and is scaling up its research and development in Penang, Malaysia. Other manufacturers such as the disk-drive maker Western Digital Inc. and audio maker Bose Corp. are also expanding operations in Penang.

Penang's reemergence as a destination of foreign direct investment is telling. The loss of PRC labor cost advantage has helped, yet other factors have burnished its credentials. Foremost is the need to diversify risk and production to avoid a devastating repeat from the recent natural disasters in Japan and Thailand. Also, Penang does not lie on the Pacific Ring of Fire, it has continued to improve its logistics infrastructure to be among the best in the region including a reliable supply of electricity and clean water, and it inherited the British legal system that better respects intellectual property rights.

A Consumer's Conversion. The culture of consumerism is deeply ingrained in our society, compelling us to spend our lives buying things we do not really need. The "end of cheap China" may very well put an end to that. We may finally realize that happiness does not come from mindless shopping sprees but from a heart that is contented and clutter-free. More importantly, it flows from a heart that is more inclined to give than to take or consume.

The "end of cheap China" may seem a tragedy. But to others, it may be a gift in disguise.

*ADB recognizes this member by the name of the People's Republic of China.