Is protectionism a viable policy option for the G20?

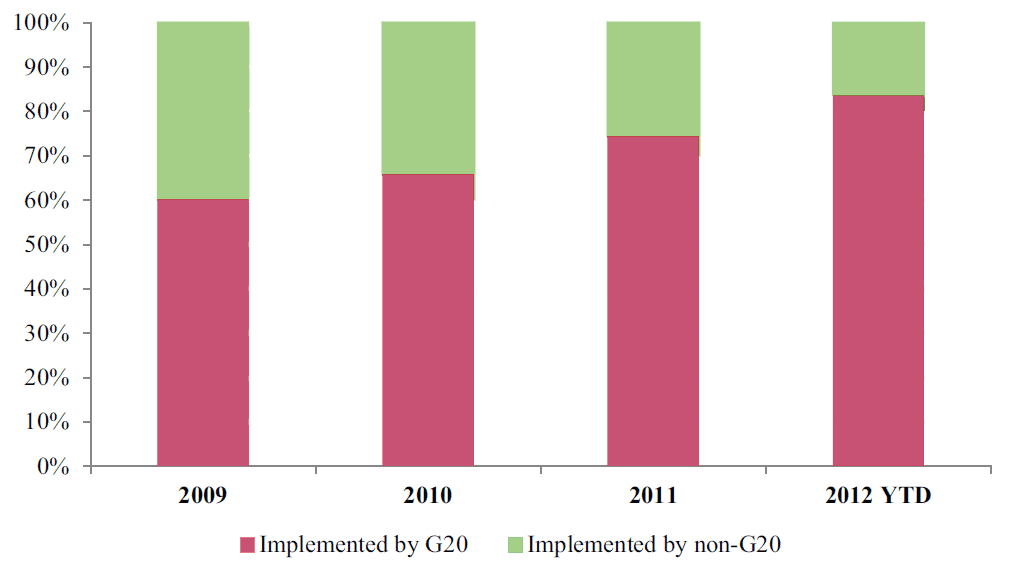

Protectionism seems to be back in favour for many policymakers in the G20. Since the start of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in September 2008, protectionist measures are reported to have outnumbered liberalizing measures by five to one worldwide. According to the Global Trade Alert the cumulative number of protectionist measures increased from 100 to 1600 worldwide over this period. The trend, although it might abate somewhat, is unlikely to halt in the foreseeable future (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Protectionist Measures Implemented 2008-2012

Source: Débâcle: The 11th GTA Report on Protectionism

What is at stake is not just less than expected growth in world trade or a slowdown in global economic growth the liberal economic order established in the second half of the twentieth century.

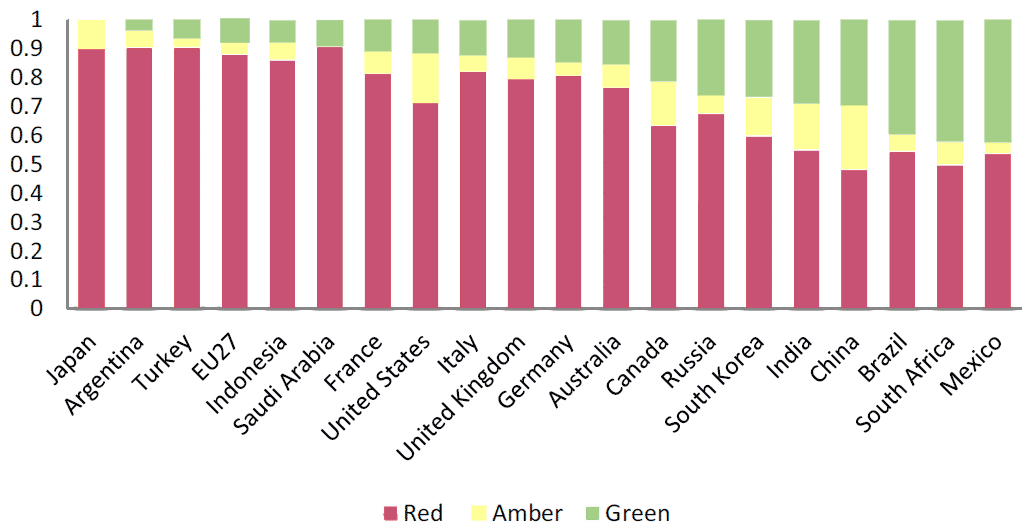

Although developed countries are not themselves the heaviest users of protectionist measures, it could be viewed as ironic by some that many of the protectionist measures enacted were taken by those developed countries that have long been advocating the benefits of free trade and investment to developing countries (Figures 2 & 3).

Figure 2. G20 Protectionist Measures Since 2009

Source: Débâcle: The 11th GTA Report on Protectionism

Figure 3. G20 State Measures Since November 2008

Source: Débâcle: The 11th GTA Report on Protectionism

While continuing to voice their commitment to resisting protectionism, developed economies have been augmenting traditional protectionist policies (e.g. agricultural subsidies) with new ones under the rubric of domestic bailouts and stimulus packages, political sensitivities, national security concerns, trade defense actions, and almost all conceivable non-tariff barriers (standards, licenses, quotas, etc.). In contrast, the ratio of liberalization to protectionist measures in the emerging Asian economies, including the People's Republic of China, is two to three times greater than those in developed economies.

As a result, emerging Asian economies have been hit the hardest by both a recession in developed economies and the corresponding protectionist policy responses. It is true that emerging Asian economies need to bear their fair share of responsibility for their current predicament. For too long, they have arguably been overly dependent on an export-led growth model with little attention to boosting domestic demand or decoupling their dependence on developed economies. In the process, they have also enacted various policies that could also be labeled "protectionist", particularly by adopting various schemes and instruments that favour exports to the detriment of imports.

Notwithstanding, both developed and emerging economies will suffer the consequences of the current wave of rising protectionism, the two most important of which include efficiency losses and a legitimacy crisis for the post-war liberal international economic order.

Protecting domestic industry or jobs no matter how politically expedient, runs contrary to the logic of a market-based economic model. A more worrying fact is that the restrictive measures taken by many countries, both developed and developing, point to a paradigm shift in foreign economic policy. Despite the supremacy of liberal capitalism over the last 50 to 60 years, it is easy to see the pendulum slowly shifting from the free market paradigm to one that relies more on a nationally planned or managed industrial policy. Among others, Pascal Lamy recently expressed similar worries.

Even if such protectionism does not deteriorate into outright trade war, it nevertheless undermines the legitimacy of the current global economic order. Those who argue that global governance mechanisms worked well during the GFC underestimate the damage done to global trade, growth, and more importantly, to general confidence. The same observers seem to be oblivious of the fact that it is ultimately members of the G20 who are responsible for 80 percent of all protectionist measures in 2012. Some might say this statistic only mirrors the importance of the G20 in global trade terms, but the truth is that the corresponding figure in 2009 was only 50 percent.

There is an urgent need to strengthen the current international economic order by making it more inclusive and applying rules more evenly across the board. Developed economies and all member countries of the G20 need to lead by example instead of resorting to protectionism. A stark observation by E. H. Carr during the interwar years would bring the point home: “At Geneva [the League of Nations meetings] I was stuck by the fact that everyone professed to believe that tariff barriers were a major cause of aggravation of the crisis, but that practically every country was busy erecting them”.