FDI in Asia’s LDCs: Unrealized development potential

According to a recent ADB survey, trade finance shortfalls in developing Asia caused companies to miss out on nearly $425 billion in commercial opportunities. Traditionally, countries with market gaps have looked to foreign aid for development assistance. But in the fallout from the global financial crisis, developing countries have seen aid levels fall by 8.9%. This is compounded by a reallocation of aid in 2012 away from the poorest countries and towards middle-income countries.

Could private capital flows help to address these financing and investment gaps? Foreign direct investment (FDI) trends in Asia suggest that it might, but data suggests that countries need to do more to enhance the development impacts of FDI.

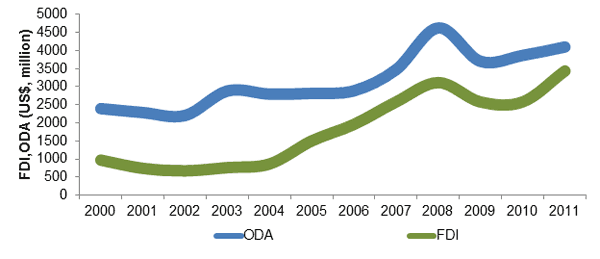

FDI flows are to LDCs rising faster than ODA

Global FDI flows have remained resilient in developing countries. For Asia in particular, while flows declined year-on-year, they were still at their second highest level in 2012. Least Developed Countries (LDCs) have particularly benefited with an annual growth rate of FDI of 16.2% from 2000–2007 compared to a developing country average of 8.7%.

Figure 1 illustrates that FDI flows to Asia’s LDCs have risen faster than ODA over the past decade. This is particularly important for LDCs and other low income states that often depend on ODA. The change in fortunes is true globally as well as in Asia. It has been most pronounced in Africa where FDI flows have exceeded ODA flows since 2005.

Figure 1: ODA and FDI to LDCs in Asia

Source: UNCTAD, 2013.

Note: LDCs in Asia include Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Nepal.

FDI flows are not a replacement for ODA, as their motivations and objectives are very different. Yet, while the theoretical relationship between FDI and aid is ambiguous, their impacts on development variables often overlap. This realization underlies the increasing integration of investment policies into national development strategies.

FDI as a percentage of GDP has grown rapidly in Asia’s LDCs, from an average of 0.96% in 1990 to 2.78% in 2011. Such growth suggests that FDI flows present LDCs with a tool that can potentially be used to transition away from aid dependence through engagement of the private sector. But according to an index presented in the 2012 World Investment Report, Asia’s LDCs are not taking full advantage of the development potential such flows present.

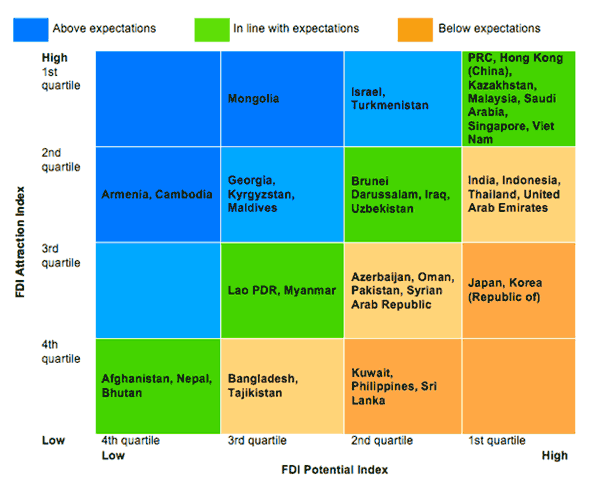

Development potential of FDI is not fully realized

In 2012, UNCTAD introduced an index that seeks to quantify the contribution that FDI makes to economic factors such as employment, taxes, wages and research & development. In short, it can help us understand how efficient countries are at capturing development potential of investment.

Figure 2 suggests that some countries are better at managing FDI than others. Some states, such as Cambodia (in blue), are attracting much higher FDI flows than their domestic economic characteristics would lead us to expect. Others, such as Bangladesh (in orange) have characteristics that suggest they should be receiving much more FDI than we see occurring.

Figure 2: UNCTAD’s FDI attraction index vs. potential index in Asia

Source: World Investment Report (2012).

Source: World Investment Report (2012).Notes:

- FDI Attraction index measures: the success of economies in attracting FDI (in total and in relation to their size). FDI potential index measures: an economy’s attractiveness to foreign investors, capturing factors (apart from market size) that are expected to have an impact.

- PRC – People’s Republic of China

Improvements to the Investment Environment will Improve Development Impact

In the post-crisis environment, developing countries find themselves in a particularly strong position with regard to FDI. According to investor surveys and 2013 World Bank Global Economic Prospects, we can expect FDI to continue to flow Southward.

This matters because where the domestic market is weak, FDI functions as a bundle of assets that can bridge numerous domestic gaps. While it is not a substitute for aid, it can play a supplemental role. There are two activities that are often missing in LDCs, but have been shown to advance the developmental potential of FDI.

First, governments can establish regular dialogues with the private sector. Such activities increase the capacity of the government to target reform and development assistance as well as to negotiate trade agreements which require technical sectoral expertise.

Second, governments can play an important matching role for foreign invested enterprises. Particularly where domestic opportunities are limited, governments can open markets simply by identifying and matching suppliers and buyers. Both of these activities require a dynamic interaction between governments and the private sector. It is through this interaction that national development objectives are most effectively advanced through FDI.