The changing global economy: Which Asian countries participate in global value chains, and why do others not do so?

An increasingly important part of international trade consists of fragmentation of the production process, with differing tasks in the global value chain (GVC) being undertaken in different locations.

East Asia has been at the heart of this process, but not all Asian economies have participated in GVCs. A recent paper traces the origins of the GVC phenomenon, attempts to measure the significance of GVCs, and analyses why some countries participate in GVCs while others do not.1

Falling trade costs as a driver

By the time the WTO was created in 1995, tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade had fallen considerably, and yet there was still evidence of a border effect. A focus of the paper was to identify why international trade was more difficult than domestic trade, and to measure these trade costs.

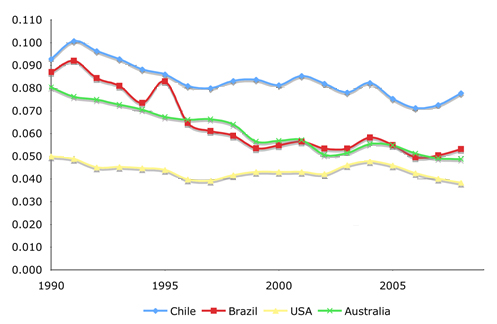

Patricia Sourdin and I have used the gap between the fob value of exports and the cif value of imports to estimate trade costs over the last two decades. Due to data constraints, our work focused on imports of Australia, Brazil, Chile and the USA; all four countries showed a steady decline in trade costs. Despite rising fuel prices and in more recent decade, the global economic crisis, trade costs fell to low levels, around 5% on Australian and Brazilian imports, lower for the US and higher for Chile.

Figure 1. Average trade costs (cif-fob gap), Australian, Brazilian, Chilean and US imports, 1990-2008

Source:Sourdin and Pomfret (2012)

Global value chains

In the 1990s, products such as the Barbie doll or electronic goods were assembled in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), but the value-added in the PRC was small. These and other goods were produced in GVCs where tasks were traded. GVCs relied on timely delivery of parts and components at every stage, with no unnecessary costs to crossing borders. To participate in GVCs, countries needed to have low trade costs, measured in money or time.

In practice, many supply chains are regional rather than global, due to advantages of proximity when face-to-face contact is required to resolve glitches. Distinctive regional value chains have emerged in North America, Europe and East Asia. The phenomenon is most pronounced in sectors such as cars and electronic goods, although GVCs have been observed in a wide variety of goods.

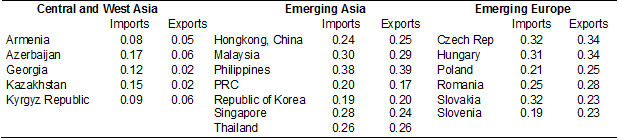

A popular way to measure participation on GVCs is to examine the share of parts and components in a country’s trade. Table 1 highlights the differences between the share of parts and components in the trade of major GVC participants in emerging Asia and emerging Europe, and the much lower shares in a region that is outside GVCs.

Table 1. Trade in parts and components as a share of trade in manufactures, 2012.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on COMTRADE data

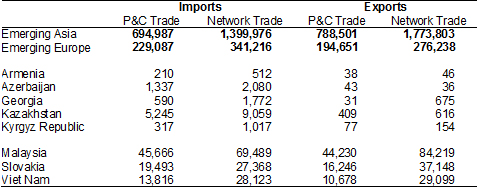

In value, GVC trade is much larger in Asia than in Europe, whether tracked by parts and components trade or by trade in the six sectors in which GVCs have predominated - what Athukorala calls “network trade” (Table 2). There is great variation in Asian economies’ GVC participation. The small number of examples from West and Central Asia found in the paper reinforces this conclusion.

Table 2. Trade in parts and components, and value of network trade, USD million, 2012.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on COMTRADE data

How can governments promote GVC participation?

There is a strong connection between low trade costs and GVC participation. The East Asian countries that are in GVCs have reduced their trade costs unilaterally, by bilateral agreements, and by joining plurilateral accords such as the WTO Information Technology Agreement.

Non-participating countries are characterized by higher costs of doing business, more obtrusive border controls, and other obstacles. Governments may be reluctant to undertake necessary reforms, and may be wary of the potential for increased volatility and inequality that sometimes accompany GVC participation. However, the cost of non-participation is falling behind in economic prosperity. Import-substituting industrialization is no longer a serious option because no country with an integrated car or computer industry can hope to be competitive with goods produced along efficient GVCs.

1 P. Sourdin, and R. Pomfret. Forthcoming. The Global Value-Chains and Connectivity in Developing Asia – with a particular focus on the Central and West Asian region. ADB Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration.

*Richard Pomfret, Professor of Economics, University of Adelaide, Australia