Can renminbi appreciation resolve global imbalances?

A faster appreciation of the renminbi has often been touted as the panacea for resolving global imbalances. While such calls have softened after the recent decline in the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) current account surplus and the world’s preoccupation over the eurozone debt crisis, it is instructive to revisit the arguments that refute this claim:

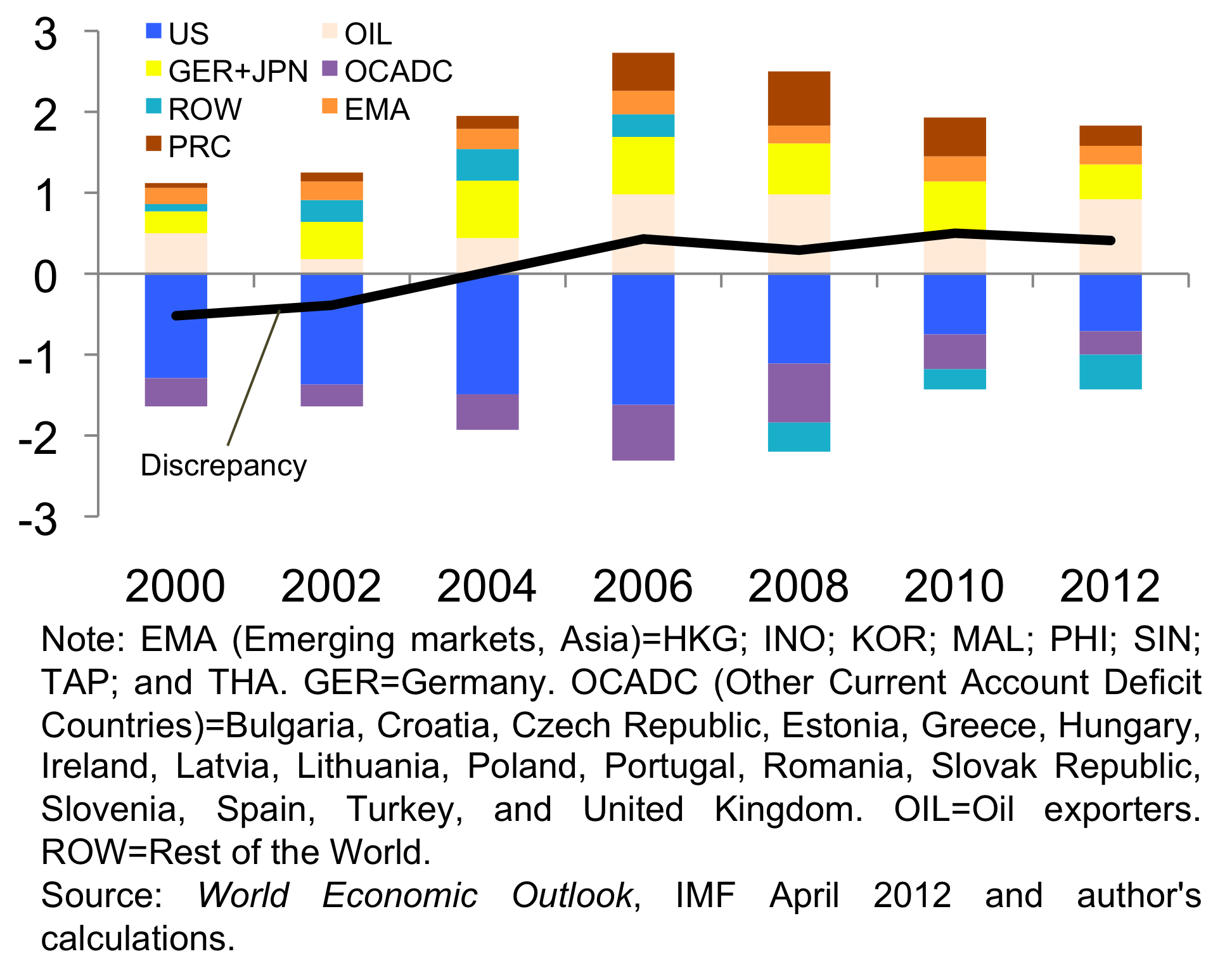

1. Global imbalances are not caused solely by the PRC. The current account surpluses of Germany and Japan combined are as large as that of the PRC. In addition, the rest of developing Asia isn’t far behind (Figure 1). In fact, the surpluses of the oil exporting countries are the largest.

Figure 1. Global Imbalances (% of World GDP)

2. With today’s fragmented production processes and global supply chains, traditional trade data can be misleading. If we measure trade on a value-added basis—excluding third country component trade—the bilateral deficit between the PRC and US could be halved.

3. There is no consensus on how much to revalue—estimates range from a 67% undervaluation to a 5% overvaluation – and on how to revalue: a one-off revaluation or gradual appreciation. Also, there is little evidence to support the claim that flexible exchange rate regimes reduce current account imbalances faster than more rigid systems.

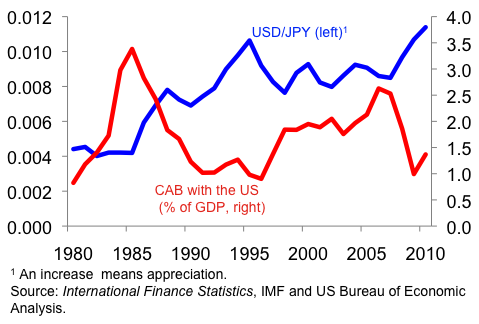

4. Revaluing the yen 25 years ago did little to alter Japan’s current account surplus. In the mid-1980s, Japan’s economic growth slowed after the two-year 51% yen revaluation (Figure 2). Still, not only did Japan’s own current account surplus persist, so too did the US current account deficit. To some, this precipitated the burst of the 1990s stock and property bubble—the effect of which is still being felt today.

Figure 2. Japan Current Account Balance (CAB) with the US versus Exchange Rate

5. Renminbi appreciation is not likely to benefit the US. If US consumers buy less from the PRC due to higher prices, they will have to buy from elsewhere at higher cost. Companies from the US and PRC generally do not compete in the same products. Also, with growing US imports from the PRC now constituting (for the most part) intermediate inputs used in manufacturing and service production rather than consumer goods, a renminbi appreciation will raise input costs. This will in turn reduce US competitiveness, resulting in potential job losses.

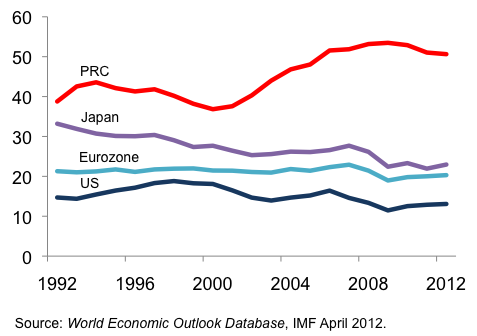

6. PRC current account surplus is a result of structural factors—not just an undervalued currency. Domestic savings reached 51% of GDP in 2011 from 36.8% in 2000 (Figure 3). Households save in part to insure their future in the absence of widely available pension, health, and education plans—and given an underdeveloped financial sector. Corporate savings share of national savings has also increased. Factors such as limitations on migrant worker benefits, regulated interest rates, capital outflow controls, state-directed credit, and fixed and subsidized energy prices all work to repress factor costs—in effect subsidizing production and investment—benefiting corporations over workers.

Figure 3. Gross National Savings

Thus, resolving global imbalances requires deep structural reforms beyond simple renminbi appreciation. PRC authorities are keenly aware of the costs associated with maintaining a large surplus. A refined development strategy that refocuses on the quality of growth—greater financial development and liberalization, more inclusive income distribution, and liberalizing factor markets, for example—will have to accompany an appreciated renminbi.

Advanced economies, of course, must do their part. Deleveraging will continue and net savings will have to rise. But harping on an overvalued renminbi may only detract from the deep structural reforms that must proceed in tandem.