Capital inflows and export competitiveness in Asia: The role of education

South Asia is the only developing region where foreign direct investment (FDI) has had a negative impact on export prices, measured by terms of trade. Recent research has shown that in most emerging and developing countries FDI generally improves terms of trade. This is good news for most emerging economies in Asia and elsewhere which have experienced periods of large capital inflows over the past decade. So what is it about South Asia (defined here as Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) that makes the region an outlier?

To explore this question, we compare two representative countries. Thailand represents the East Asia region (defined as the People's Republic of China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand) where FDI has positively impacted export prices and Bangladesh represents the puzzle of South Asia. We focus on the role of human capital which impacts both the type of FDI that is attracted and also the ability of the domestic economy to absorb spillovers, which in turn will affect export prices.

A Tale of Two Countries

When globalization started to kick off in 1980, 66.8% of the Bangladeshi population above 15 years had no schooling experience, only 0.5% had completed tertiary education, and the average years of schooling were 2.25. Currently, almost one quarter of FDI stock is accumulated in textiles, which is also their primary export sector. Bangladesh's top three export goods are different categories of textiles and account for over 70% of all exports. Even so, Bangladesh remains a small country exporter in which none of its main exports have a world market share of more than 3.5%.

By contrast, in Thailand, over 85% of the population above 15 had some schooling experience in 1980 and 2.8% completed tertiary education. The average years of schooling were 4.4. Thailand's current FDI profile is also very different from Bangladesh. It has attracted considerable inflows in technology intensive sectors such as motor vehicles, electrical equipment, electronics/optics and plastics. The most important export sectors were more technology intensive as well, often benefiting from accumulated capital formation. Thailand gained a world market share of over 10% in all its 10 most relevant export sectors despite being a small country with a relatively well-diversified export structure.

The Role of Education

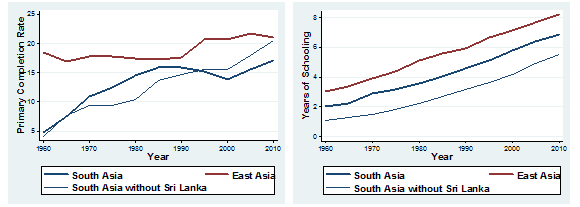

Educational attainments differ considerably between South and East Asia in general. East Asia achieved much higher rates of primary education and average years of schooling compared to South Asia, for example; especially when not considering the outlier of Sri Lanka (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Primary Education Rates and Years of Schooling in Asia (1960-2010)

Note: Values computed as unweighted averages for Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (South Asia) and for People's Republic of China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand (East Asia).

Source: Barro and Lee (2010).

This data suggest that the generally positive impact of FDI in terms of trade may operate via education. In fact, the above-cited research shows that developing countries with below-average years of education – such as Bangladesh — experience a negative relationship between FDI and terms of trade while those above the average — such as Thailand — exhibit a positive one. This might explain the negative relationship we observe in South Asia.

In South Asia, relatively low levels of human capital force producers to focus on easily substitutable export products, where competitiveness can mainly be gained via low prices and where wages can be held low because of a considerable unskilled labor reserve.

As a result of the low knowledge content of its export basket, products can be easily reproduced, thus making it difficult to acquire a strong market position. In fact, South Asian economies such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, or even Pakistan do not reach world market shares of more than 7 % in any product group.

East Asia, on the other hand has benefitted from higher levels of human capital which has enabled the region to specialize in higher segments of the value chain. Because of the knowledge content in these products, they are not easily reproducible, enabling exporters to gain world market shares with the according pricing power: Thailand and the People's Republic of China hold over 10 % and 40 % of market share in all of their 10 main export products respectively.

Since FDI is motivated by exploiting comparative advantage and corresponding production factors, it intensifies a country's mode of world market integration. This helps explain why FDI in South Asia had a negative impact on export prices while it had a positive impact in other emerging and developing countries. Its positive effects on productivity translated into lower prices in the former case but operated via product-upgrading and accordingly higher revenues in the latter case, as other recent empirical evidence also suggests.

Policy Conclusions

The story of these two regions highlights the need to interpret FDI through the lens of local factors, such as human capital. In addition to reminding us that education is not a necessary byproduct of FDI, this relationship highlights the importance of pro-active development policies, which especially fosters human capital development in the early stages of globalization. This will enable countries to both attract higher-value FDI and to absorb more benefits from it.