How Technology Can Turn Asia’s Aging Workforce into an Advantage

Introduction

Asia needs to harness technology to overcome the negative consequences from a contracting and aging workforce, while maximizing the benefits of longevity for inclusive and sustained economic growth.

Experience from countries in the advanced stage of demographic transition shows that it is feasible with greater policy attention and more proactive and innovative measures. Countries in Asia and the Pacific at the forefront of aging are encouraged to continue promoting innovation, adoption, and the diffusion of age-related technology and lifelong learning, and to provide working environments conducive to senior workers. Similarly, it is critical for countries with young and growing populations to invest in human capital even if aging and technological change are expected to arrive at a slower pace.

This policy brief was adapted from the Asian Development Bank’s report, Tapping Technology to Maximize the Longevity Dividend in Asia (link is external).

Aging and Demographic Transition in Asia: Impact on the Workforce

Asia and the Pacific is aging at a fast pace. The population share of seniors aged 65 and over increased from 6% (209 million) in 2000 to nearly 8.3% (349 million) in 2017, and it is projected to reach as much as 18% (870 million) in 2050. Countries experiencing a surge in the share of seniors toward 2050 include the Republic of Korea (14% in 2017 to 35% in 2050), Singapore (13% to 34%) and Thailand (11% to 29%), while that of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is expected to grow from 11% to 26% in the same period.

Rapid aging will leave its mark on the workforce population. The share of working-age population (15–64) in the region will no longer grow and plateau at around 67% from 2017 to 2030. Economies likely to see a large contraction of working-age population during this period include Hong Kong, China (10.4%), the Republic of Korea (10.3%), and Japan (8.7%). The region’s working-age population itself is graying and its average age is expected to rise from age 37 in 2015 to 40 in 2050.

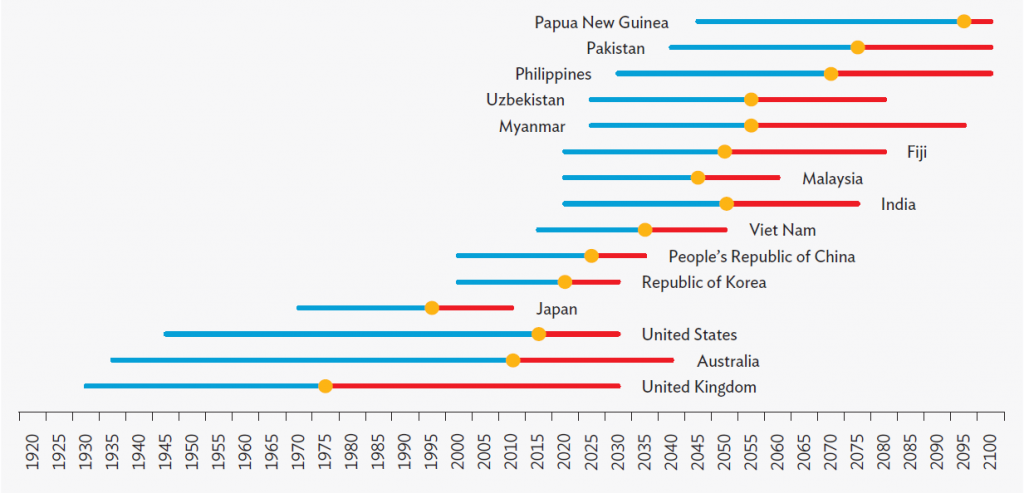

Figure 1: Speed of Aging

Note: The blue line refers to the projected number of years for the share of the population of age 65 and over to rise from 7% to 14%. The red line refers to the projected number of years for the share of the population of age 65 and over to increase from 14% to 21%.

Source: ADB calculations using data from the United Nations, Department of Social and Economic Affairs, Population Division.

An economy is considered “aging” once the share of its senior population hits 7%. Over time, its senior share of total population will breach the 14% mark, at which point it is considered “aged,” and “superaged” once the share reaches 21%. The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific provides a definition for aging, aged, and super-aged societies(link is external).

Innovation to Weather Demographic Headwinds

Technology and innovation play key roles in helping tackle the challenges posed by a declining and aging working population. These are:

- improving health and extending longevity,

- transforming work and the workplace, and

- creating a supportive environment for workers and improving the functioning of labor markets.

All contribute to boosting labor force participation and productivity. Rapid technological advancement can further contribute to ensuring that jobs are age-friendly and to improving human capital of the workforce through enhanced health, education, and skills.

Table 1: Types of Technological Solutions to Aging Labor Markets

Type of Technology | Examples |

Technology for health and longevity | Biotechnology, automated diagnosis, surgery and therapies. The internet of things (medical equipment and wearable devices), and health-related big data analysis. |

Technology for transforming work and workplace | Industrial robots, automation, AI, machine learning, and remote/telework platforms |

Technology for workers and supportive labor market infrastructure | Remote and virtual education and training, human resource and age diversity management, cloud-based job matching service; ergonomic and human function aiding devices at the workplace (adaptive technologies). |

Source: Authors.

Aging and soon-to-be aged countries are encouraged to allocate sufficient funds to research and development to promote innovation and the adoption of suitable technologies and to invest in human capital and resources development, particularly in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (International Monetary Fund 2016). This point is particularly salient for soon-to-be aged countries that anticipate having to spend more on pensions and healthcare. Countries are also encouraged to foster innovation by protecting patents and licenses and by creating a business environment and economic infrastructure attractive to the private sector.

Seniors can be a rich source of productive workers, especially among countries progressing to aging and aged societies. There is a scope for encouraging work participation of seniors, given that healthy life spans are increasing, and working environments and labor markets are accommodating their needs and work preferences. Intensive use of machinery and automation has made many jobs and tasks less physically demanding and more accessible to older workers, helping them stay in jobs beyond normal retirement age. Senior workers also prefer flexible and part-time arrangements, tasks that exploit their experience and knowledge, and work that provides a meaningful social space and a sense of contribution and fulfillment.

The right incentives can readily draw seniors into returning to the labor force. Existing policies must be reviewed to remove disincentives to work and add more benefits for those who choose to work after reaching legal retirement age. Working conditions and environments should be reviewed to accommodate the preferred working style of senior workers. Investing in relevant technologies, such as cloud sourcing that help match jobs and tasks with skills, has great potential to cultivate the latent senior workforce. More effort should also be made to create an enabling policy environment for elderly labor force participation, such as removing age-related aversion in hiring (OECD 2015).

Raising Productivity of Aging Workforce via Technology

The key channel through which countries can harvest the longevity dividend is raising the productivity of seniors in their workforces. Elderly people are better educated than in the past, so they can carry out high value-adding tasks and work with complementary technologies. Their productivity can also be enhanced by continuing investment in skills development and by developing technologies, such as human resource management tools that aid physical and cognitive capacities and help seniors and aging workforces perform better as a whole.

However, skills development opportunities for seniors remain limited, and many are reluctant to take them up due to age-related concerns. Thus, training programs that consider the special learning needs of the elderly should be made widely available. The importance of lifelong learning cannot be overemphasized in anticipation of greater longevity and extended working years. Given that the types of skills needed for future jobs are unpredictable, job training should not merely focus on skills relevant for today’s jobs. Old curricula need a thorough review to incorporate an element to build the capacity of workers to “learn to learn” new skills. Tapping technological solutions for education, from customized online courses to more engaging and participatory platforms such as game and simulations, can produce solid learning outcomes at affordable cost, but their impact must be carefully evaluated.

The “gray divide,” the gap between technology and the ability of seniors to use it, is gradually being filled as new generations of seniors become more technology-savvy. However, more work is needed to better connect elderly workers to available and emerging technologies. Examples include better information outreach and improved user-friendliness of services and devices. Age-friendly technological advancement can also be promoted through public and venture capital investments that fund initiatives to change the way seniors work in future.

Regional Cooperation to Gain from Diversity in Labor Force Endowment

Lastly, the Asia and Pacific region consists of countries with varying demographic profiles, among them young and populous countries that can complement the demographic transition in aging countries. To gain from potential complementarity, countries in the region need to collaborate and invest in connectivity, as well as in developing human capital.

Countries can strengthen their collaborations to facilitate cross-border labor mobility through the development of multilateral skill and qualification recognition programs and region-wide mobility (brain circulation) schemes for skilled professionals. They can also work together to reduce barriers to mobility, such as high migration costs.

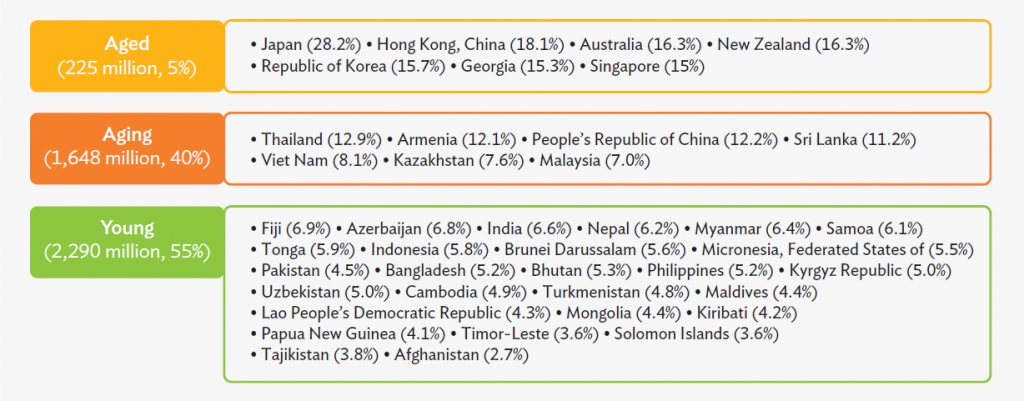

Figure 2: Economies by the Stages of Aging in Asia and the Pacific

Notes: Figures in parentheses for every aging group refer to the total population stock and the share to the total population in Asia and the Pacific. Figures in parentheses after every economy refer to the senior share of the population in 2020. Japan has been a “super-aged” economy (that is, senior share of its population is at least 21%) since 2008.

Source: ADB calculations using data from the United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; and the World Bank, World Development Indicators (accessed March 2017).

Original article was published at the Development Asia blog and duplicated here with permission from the author. *