PRC’s financial policy menus and slower growth

As the global economy has shifted over the past decade, emerging economies are faced with novel opportunities and challenges stemming from their newfound leadership. Given the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) new economic direction with the resulting slower growth, and the inevitable headwinds from ongoing global changes, it is important to investigate what financial policy items should be on their plate and what the implications are for the rest of Asia.

Inflation, Exchange Rate, and Financial Losses

The aims of the People’s Bank of China’s (PBC) are to fight inflation and keep the foreign exchange market in equilibrium. Many argue that the best course of action is to allow the Renminbi (RMB) to float. Most studies however have mixed or inconclusive findings on whether floating will ease the People’s Bank of China’s (PBC) burden to meet its stated objectives. Only a few have found statistical evidence to show that the RMB is actually undervalued. Additionally, the effect of RMB appreciation on inflation is equally unclear. Let’s look at the reality.

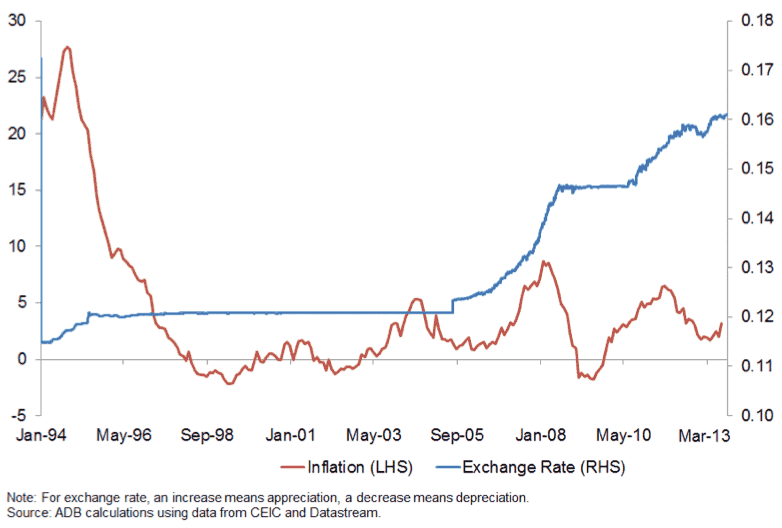

During the fixed exchange rate period of 1994-2004, efforts to limit inflation were effective (see Chart 1) until outside pressures and market expectation for RMB to appreciate mounted. At this point, inflation started to creep up and turn volatile. Since then, large capital inflows and an increase in PRC’s surplus has intensified the pressure on RMB, forcing around 6% annual appreciation. Thus, it remains unclear whether RMB appreciation will guarantee a lower inflation.

It is, however, much clearer that the valuation effect of appreciation can bring financial losses. Being a surplus country, firms and agents in PRC hold dollar assets. Unable to unload these assets due to currency mismatch implies that firms’ financial conditions would have been deteriorating (also known as "conflict of virtue"). It is the policy bias favoring profits than wages that prevents the balance sheet from worsening. If the new policy gradually removes such bias, and it should, firms’ profit and economic growth cannot be maintained high.

Chart 1: CPI Inflation (y-o-y %) & Exchange Rate: PRC

Alternative Policy Menus: Outflows, RMB Internationalization, Swaps, and Capital Markets

Being the largest recipient of capital inflows, a continued pressure on RMB to appreciate is inevitable. The standard response has been a sterilized intervention. But that will worsen PBC’s portfolio position. So, what are the alternatives?

Outflows

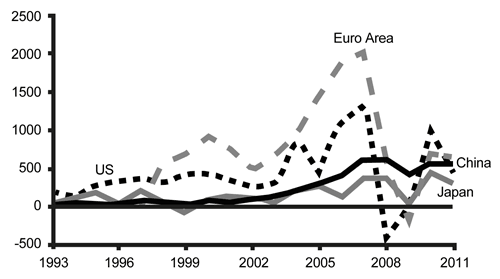

The growing burden of PBC’s interventions in the foreign exchange market could be softened, at least partially, by removing some restrictions on capital outflows. Capital outflows from PRC have increased with low volatility even during the crisis (see Chart 2). Further ease of capital outflows should be on the policy menu.

Source: Institute of International Finance

Source: Institute of International Finance

RMB Internationalization

But outflows alone would not be sufficient. PRC’s problems of currency mismatch due to its inability to lend in its own currency remain. Greater international use of RMB should be targetted. The size and influence of PRC in the global economy make it natural to expect increased use of RMB in international transactions. Some central banks have already begun to keep a portion of their reserves in RMB (e.g., Malaysia, Chile, Nigeria) despite the fact that it cannot be treated like regular reserves due to RMB’s lack of convertibility. Estimates suggest that by 2015 PRC’s trade settled in RMB may reach 20 percent.Greater acceptance of the RMB as a trade settlement currency will also have important implications for financial market interactions in the region. As investment currency, RMB’s share has been steadily increasing. Offshore RMB deposits are estimated to reach RMB 1.5T, and the issuance of RMB-denominated bonds in Hong Kong, China is also on the rise.

Bank transactions in RMB have been increasing; and so has the regional and international presence of PRC banks outside Hong Kong, China. PRC has also signed agreements with countries as diverse as Argentina and the United Arab Emirates to expand its banks’ operations. To promote efficiency in the offshore RMB market, PRC’s plan to have a single centralized cross-border RMB payment infrastructure and launch an international payment system (CIPS) in 2014 is a positive development in this direction.

Swaps

Establishing swap lines to make other countries’ central banks comfortable with RMB-denominated instruments is another important step to take. It has twin benefits: boosted RMB internationalization, and stabilized currencies. In order to grow local currency swaps, PBC has established local currency bilateral swap lines with other central banks around the world. Following the G20 meeting in Los Cabos, Mexico, it was agreed that financial safety nets would be established to mitigate the risk of contagion from external shock.

The good news is that PRC still has fiscal policy space should the external environment worsen. The existing high reserve ratio can also be used to counter the dampening effect on domestic demand without threatening inflation. The bad news is that the remaining internal rigidities such as low effectiveness of monetary and financial policy due to sizeable operations of shadow banking may stand in the way of making the policy outcome sustainable. Dealing with shadow banking, however, warrants economic growth to slow.

Capital Markets

Growing public demand for financial services including shadow banking indicates a need for capital markets to develop further. The policy of giving banks more flexibility in setting interest rates is a move in the right direction. This will allow prices to play a greater role in clearing the capital market. As PRC’s role and influence in the world economy grows, capital markets need to be better integrated with the international market.

For this to happen, policies to ensure long-term investment stability are needed. Raising the limits on investment in the stock markets by foreign institutional investors is one strategy. Quotas for exchange-traded funds raised offshore that can be invested in domestic capital markets is another. A further sign of liberalization announced in 2012, was to allow Hong Kong, China’s banks to lend RMB directly to three special economic and financial zones in Guangdong province.

Gradual liberalization is also occurring in the bond market. Although government bonds remain the most popular, corporate bonds have grown more steadily. This trend is likely to continue due to efforts made by officials to improve market infrastructure.

Bottom Line and Implications for the Rest of Asia

PRC is clearly at a crossroads between the need to implement reforms that would require economic growth to slow down and trying to avert further downward pressure from increasing global headwind. The bottom line for policy direction is to allow for more flexibility by using a mixture of policy measures, while responding to external shocks counter-cyclically.

What are the implications of the above policy menus for the rest of Asia? While Asia weathered the recent GFC quite well, signs have emerged that the region’s vulnerability has increased as global uncertainty has also increased. The International Monetary Fund’s Christine Lagarde pointed to the risks emerging in different parts of the world including "the potential "spillover" effects for Asia." If the policy menus discussed above can be effectively implemented, they will help Asia’s biggest economy to weather the slowdown in global growth, minimize spillover effects, and allow the country to meet most of the 12th five-year plan targets.

As the interdependence between PRC and the rest of Asia intensifies, this will also have positive impacts on Asia. But make no mistake, these policies and other structural adjustments definitely warrant slower PRC growth. The rest of Asia may need to start working on strategies and policies under this "new normal."