Services trade in Asia: opportunities and challenges

In 2008, RuralShores, India's leading rural business process outsourcing (BPO) company, established its first BPO center at Bagepalli--a drought-prone town outside Bangalore. Thousands of Bagepalli villagers, mostly unemployed graduates and women, who would otherwise stay unemployed or be working as farm hands, now provide back-office services to several Indian government departments, major Indian companies, and US-based firms. The rise of BPOs in unknown small villages in Indiaa> has started a technological revolution in the countryside, transformed rural employment landscape, and brought about social change.

Greater employment opportunities and improved standards of living are just some of the economic contributions of services trade. These gains are also observed in the rise of services trade in other sectors such as health care, construction, and education. Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore are major exporters of health care, providing quality health services to developing countries in Asia. These countries, including the People's Republic of China (PRC) and Indonesia, are also the world’s top traders in construction services, an important source of remittances for Asia’s emerging economies.

Trade in education services is also on the rise. International students have grown substantially in a span of three decades, from 0.8 million worldwide in 1975 to almost 3.7 million in 2009. The majority of them are from PRC, India, and the Republic of Korea. Similarly, the crossborder mobility of institutions is also increasing. Malaysia, Singapore, and Hong Kong, China host branch campuses of a number of US and European universities. More Asian students are now enjoying a higher quality of education that may not be readily available in their home countries.

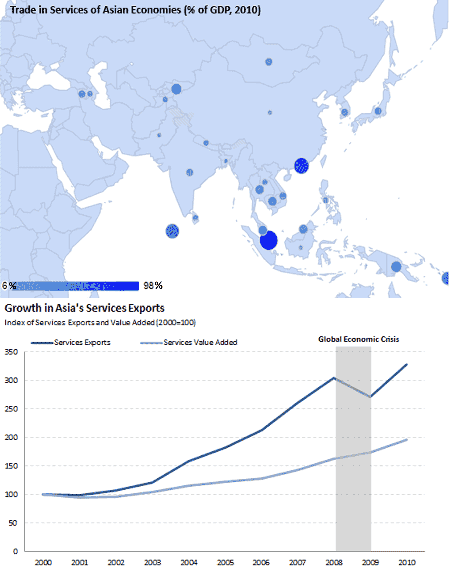

Despite the significant contributions of services trade to the economy and human development, it comprises only a small share of GDP and exports of services make up only a small share of services value added (Figure 1). This means that integration of Asian economies to the global services markets remain limited. Services exports have grown faster than services output, however, highlighting its strong growth potential and the trend towards greater integration of services markets over time.

Figure 1: Services Trade in Asia

Source: World Bank Data Bank

Major Barriers to Services Trade

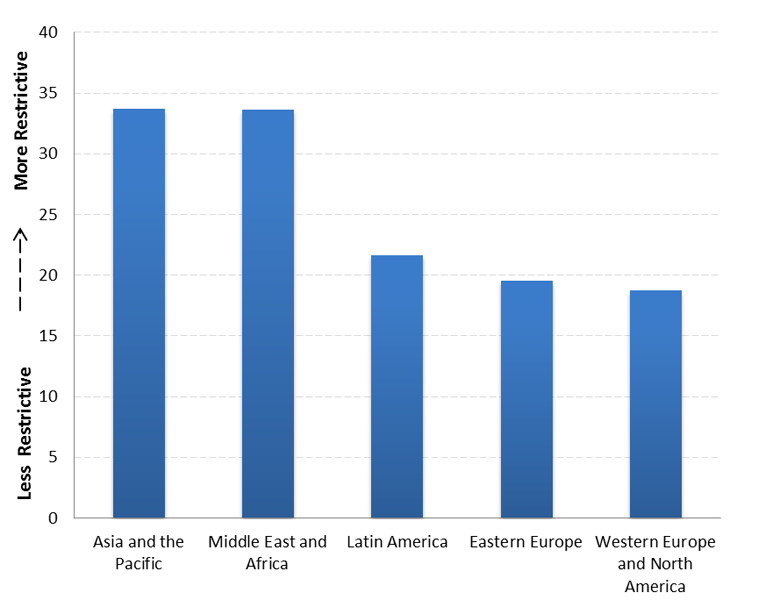

The World Bank Services Trade Restrictions Index shows that services markets in Asia are relatively more restrictive to entry of new service providers compared with other regions (Figure 2). Such restrictions include limitations on market access, national treatment and commercial presence.

Figure 2: Services Trade Restrictions Index

Source: World Bank Services Trade Restrictions Database

Market access limitations to foreign companies may take the form of restrictions on ownership or number of suppliers in a sector while national treatment impediments include special requirements on business registration, technology-transfer, and quality standards that only apply to foreign entities. Restrictions on the establishment and operation of commercial presence by foreign companies may entail serious repercussions if the services cannot be delivered through cross-border supply such as health care.

Barriers to services trade do not end at the border. They may also arise through burdensome and opaque regulatory measures that exacerbate transaction costs and business risks. For instance, in construction services, the process of securing a building permit is an administrative maze in most developing countries.

Key Policy Considerations

The opportunities and challenges of services trade in Asia need to be emphasized because most of the attention in multilateral trade negotiations is focused on liberalization of agriculture and manufactured goods rather than services. It was only recently that WTO Director-General Pascal Lamy called for services to be "at the heart of the trade agenda" and, for such initiative to be meaningful, it should eventually translate to concrete policy actions.

The anticipated influx of new service providers due to liberalization often entails adjustment costs such as closure of businesses that cannot stand greater competition and the resulting job losses. This suggests that market opening should be done in phases, and, where feasible, social safety nets should be put in place to aid workers and firms adversely affected by the process.

Regulations are necessary to maintain the quality of services and restrain anti-competitive practices. It is essential, however, that regulations be designed to achieve their legitimate policy objectives with minimal discriminatory effects and without unduly restricting trade. An overall regulatory framework and periodic audits of service regulations are crucial in monitoring market openness and assessing the effectiveness of regulatory measures.

Highly skilled and educated workers are important to the development of the service sector. This can be achieved through better education policies and institutions with support from both government and private sector including domestic and foreign firms. Lastly, adequate infrastructure development is vital in sustaining the rise of important service sectors such as the BPO industry, health care, and tourism.