Viet Nam’s participation in free trade agreements: History and the way forward

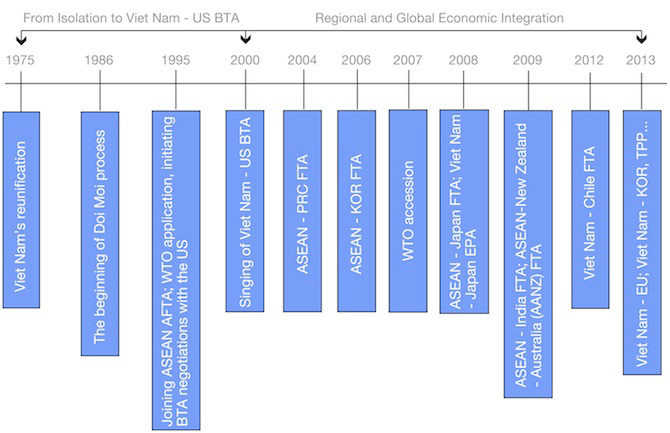

Viet Nam’s integration with the global economy and economic liberalization began in 1986 with the ’Doi Moi’ initiative. Since then, Viet Nam has become more active in regional economic integration. Here, we ask how Viet Nam has performed in terms of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), and what are the steps it should be taking to continue to benefit from integration initiatives?

Even though Viet Nam applied for World Trade Organization (WTO) membership in 1995, it wasn’t until 2001 that the country focused on WTO accession after successfully signing a bilateral trade agreement (BTA) with the United States (US). Although the BTA was seen as a stepping-stone toward WTO accession, the US proved a tough counterpart during bilateral negotiations for Permanent Normal Trade Relation (PNTR) status.

From 2001 to 2006, Viet Nam relied on the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) for progress on regional integration. After successfully becoming the 150th Member of WTO on January 2007, Viet Nam has refocused its efforts towards regional integration.

Figure 1: The Economic Integration Process of Viet Nam

Note: PRC: Peoples Republic of China, KOR: Republic of Korea

Source: Synthesized by the author, information available at wtocenter.vn and www.wto.org

Viet Nam’s participation in FTAs

FTAs are reciprocal and inclusive in nature. To minimize its exclusionary effects towards non-parties, Viet Nam has been joining FTAs, both collectively as a member of ASEAN, as well as unilaterally.

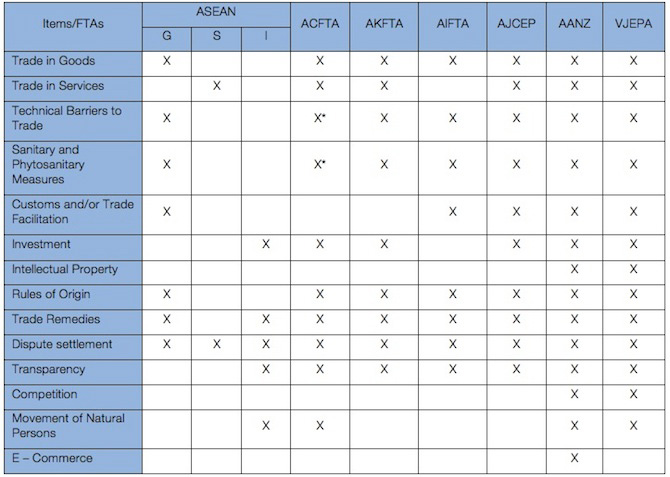

Viet Nam’s FTAs coverage has evolved to cover not only the movement of goods, but also trade in services, investment and other trade-related aspects. As shown in figure 2, the agreement establishing the ASEAN-Australian-New Zealand Free Trade Area (AANZFTA) has been the most ambitious of the agreements Vietnam has signed. This is different from other ASEAN+1 FTAs which were structured by a framework followed by specific agreements. All items in AANZFTA were signed under one single comprehensive document.

Figure 2: Main Content of FTAs signed by Viet Nam

Note: G = Goods, S = Services, and I = Investment X*: The agreement refers to non-tariff barriers in general.

Source: Synthesized by the author from legal texts of Vietnam’s FTAs.

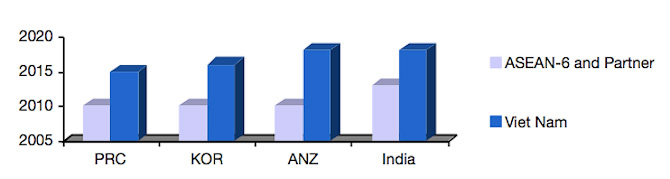

Viet Nam has benefited from FTAs

Exporters in Viet Nam have benefited from the enlargement of export markets as well as reduced tariff and non-tariff barriers, thanks to FTAs. Figure 3 indicates that Viet Nam was also given longer implementation periods for tariff reduction/elimination compared to ASEAN-6 and its FTA partners. In addition, through FTAs among ASEAN and its partners, Viet Nam has been recognized as a full market economy by India, Australia and New Zealand. This proliferation of FTAs has enabled Viet Nam to take part in deeper regional economic integration.

Figure 3: Implementation periods for tariff reduction (NT1) in ASEAN+ FTAs

Note: PRC: Peoples Republic of China, KOR: Republic of Korea, ANZ: Austraila and New Zealand

Source: Multilateral Trade Department, Ministry of Industry and Trade of Vietnam.

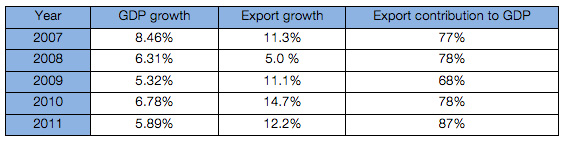

Exports drive GDP growth, and accounted for 87% of GDP in 2011.

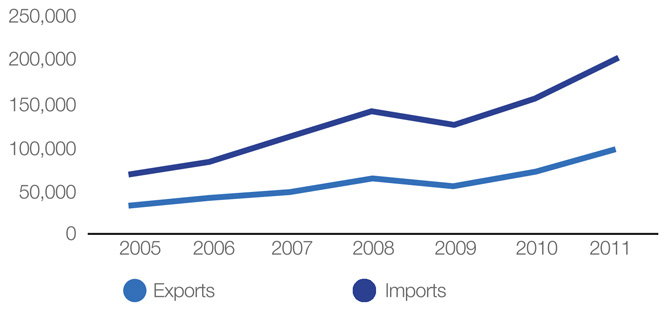

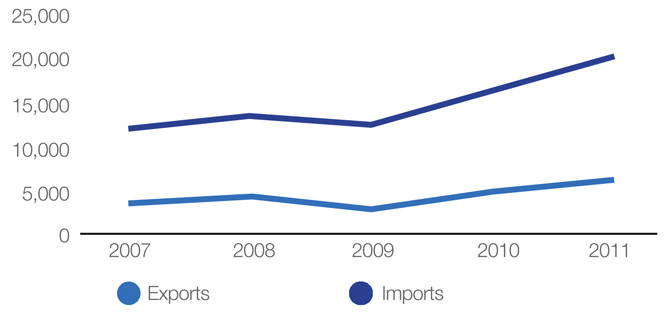

As indicated in figures 5 and 6 below, while exports have increased, imports have grown even faster, resulting in a trade deficit between 2005 and 2011.

Figure 5: Viet Nam’s Exports and Imports on Goods to World (in USD Millions)

Figure 6: Viet Nam’s Exports and Imports on Services to World (in USD Millions)

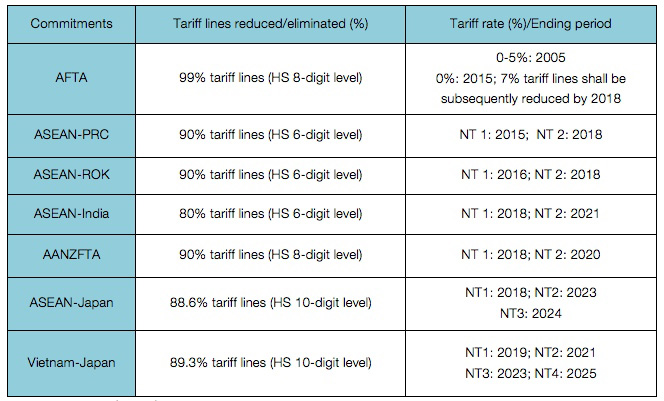

Viet Nam’s liberalization in the goods trade is often higher than its WTO commitments. Meanwhile, the country’s liberalization in services and investment generally do not exceed WTO levels, and is only compliant with the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)+. As such, the current account deficit could be cause for concern, especially starting in 2015 when Viet Nam eliminates or reduces tariffs for its FTA partners (see details in figure 7). In addition, many Vietnamese exporters have been unable to utilize the complicated and overlapping rules of origin, which negatively impacts the competitiveness of Vietnamese products.

Figure 7: Aggregation of Viet Nam’s FTAs commitments on tariff reduction

Notes: NT: Normal Track, PRC: The People’s Republic of China, ROK: Republic of Korea

Source: Multilateral Trade Department, Ministry of Industry and Trade of Vietnam.

For the time being, Viet Nam is pursuing several FTAs, including the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a US-led initiative. It has been 12 years since the Viet Nam-US BTA was signed and it appears Viet Nam wants to pursue a more ambitious FTA in which the US, its biggest trading partner, participates.

Moving Forward

FTAs are increasingly seen as building blocks towards a multilateral trading system that is currently at an impasse. The coverage of future FTAs is likely to widen to regulate WTO+ issues in which Viet Nam still lacks the capacity and resources to negotiate or implement.

In preparation for future regional integration, Viet Nam could clarify the current negotiation strategy to include requests for longer periods of implementation or technical assistance from more developed partners.

Viet Nam might also consider developing a strategy to diversify its export markets and improve its trade balance. For example, support for domestic firms to supply the raw materials for clothing and shoe products would not only be beneficial for exports but could also reduce the trade deficit. In this regard, a strategy to develop the competitiveness of domestic industry is also needed in order to compete with foreign products, especially from 2015 onwards.