What is holding back trade-driven growth in fragile states?

On June 20, 2014, leadership of the g7+ group of fragile states passed from Timor-Leste’s Emilia Pires to Sierra Leone’s Keifala Marrah. This transfer suggests that Timor-Leste’s leadership of the fragile states group in the international community has matured as the community of fragile states has consolidated their objectives.

But even as the profile of fragile states has increased on the international stage, many, Timor-Leste included, continue to struggle to promote trade and investment. In a geographic region where trade is an engine of growth, this presents an interesting question – why isn’t trade driving growth in fragile states?

To answer this, we use the experiences of two states which have gained independence this century and which expected to, but have struggled with engaging their rich, natural resource wealth. The case of Timor-Leste, in particular, suggests that the potential of trade in fragile states will lag behind the rebuilding of human capital even in resource-rich states.

Natural resource exports have great potential to drive growth

Both Timor-Leste and South Sudan began independence in 2002 and 2011, respectively, with an established export base and positive expected revenue stream. This was no accident, since we know that countries that are deeply reliant on revenues from natural resources are prone to secessionist movements . And indeed, both Timor-Leste and South Sudan conveyed post-independence plans that were founded on the expected revenue from petroleum exploration and eventual export.

When resources are well-managed, natural resource exports can provide a solid foundation for new states. In Timor-Leste, export volumes skyrocketed after oil exploration got underway. Its GDP is driven almost wholly by oil exports. It has increased from US$489 million in 2003 to US$1,079 million in 2004, reaching US$6,129 million by 2013. To harness the benefits of this revenue, the government set up a sovereign wealth fund to capture the revenue generated by natural gas reserves. This fund has been used primarily for rebuilding physical infrastructure.

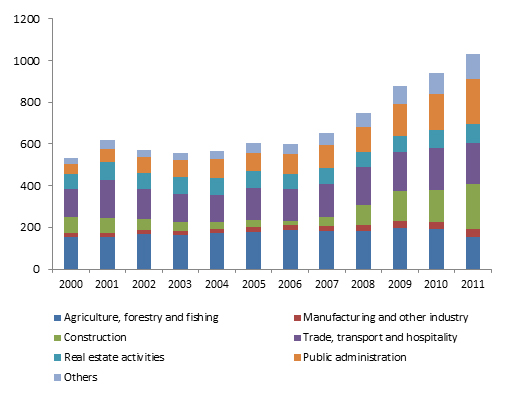

Yet, diversification of exports is also needed to ensure development is sustainable. Both Timor-Leste and South Sudan continue to struggle in their efforts to diversify production. The oil sector accounts for a bulk of the economy, at about 80% of GDP for both countries. While Figure 1 shows that Timor-Leste’s non-oil exports have been on a steady rise, they remain dwarfed by oil exports.

There are of course many factors that are holding back diversification in new states. But one in particular has persistent impacts on the business climate and which is often under-weighted in discussions of business climate improvement.

Figure 1. Timor-Leste’s Non-oil sectoral contribution to GDP

(In millions US$)

Source: Timor-Leste National Accounts 2000–2011, Ministry of Finance of Timor-Leste

Small states struggle more than others with human component of independence

Newly independent resource-rich states begin life with substantial physical capital potential. However human capital is limited even before independence in these countries by the small size of their populations. As of 2012, Timor-Leste registered a total population of only 1.2 million people with a median age of 16.6.

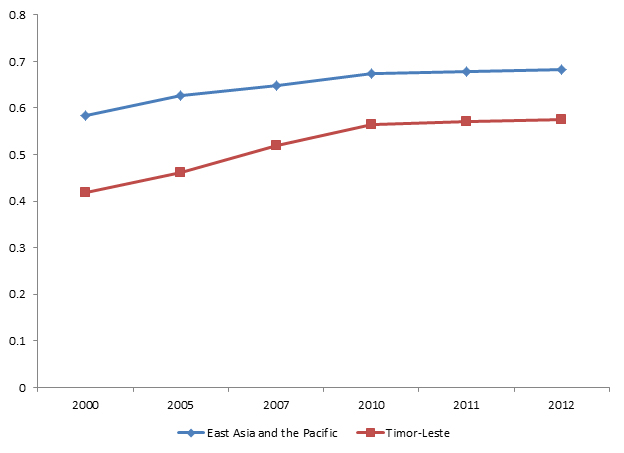

Small population size is compounded by the fact that, often, lead up to independence includes conflict, population displacement and disruption of education. For Sudan and South Sudan, at least 1.5 million people are thought to have lost their lives and more than 4 million were displaced in the 22 years of warfare that led to independence. Almost a quarter of Timor-Leste's population died during 24 years of civil war, and 80% of the country's government buildings and infrastructure were destroyed. Human capital is slow to rebuild. Figure 2 shows that while Timor-Leste’s HDI is coming closer to the regional average, in the 10 years since independence, it has changed only from 0.418 in 2000, to 0.576 in 2012.

The human component of development in fragile states is a primary focus of resilience-building efforts. However, it is rarely linked to trade-building efforts. Yet, there are important synergies. Becoming part of the international economy is one facet of nation and state building. Human resources are needed to accede to the World Trade Organization, negotiate free trade agreements and join regional groupings like ASEAN. Addressing trade-related issues and developing an international trade strategy will require solid institutional foundations, supported by technically skilled personnel.

Figure 2. HDI (0-1): East Asia and the Pacific and Timor-Leste

Source: UNDP (2013)

At the end of the day, fragile states require a different development model

For fragile states that have been fortunate enough to have the boon of resource wealth, trade can be an important early driver of growth—as in the case of Timor-Leste. But to sustain and diversify around this growth, the human component must be taken explicitly into account. In conditions of fragility, trade alone cannot result in development.