WTO dispute settlement: A right to a day in court for all

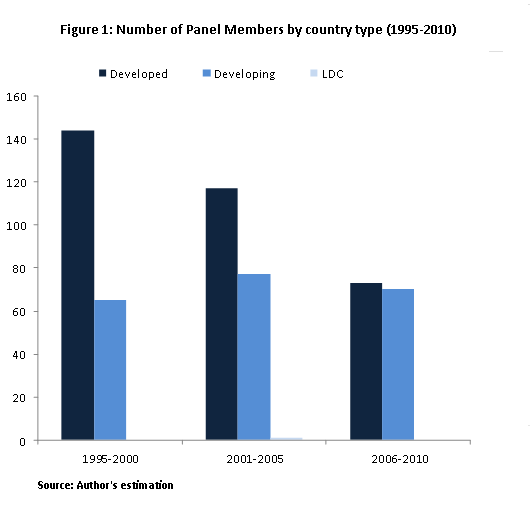

In the 17 years that the WTO has existed, only one least developed country (LDC) – Bangladesh – has ever brought a complaint before the WTO dispute settlement system. Likewise, LDCs have been almost entirely absent from the two bodies that render decisions on disputes. Of 244 total panellists in the history of the WTO, there has been only one LDC – again from Bangladesh – and no LDC has ever been invited to sit on the Appellate Body (see Figure 1).

The lack of participation of some members – small developing countries and LDCs in particular – does not mean that the WTO dispute settlement system is not a success. Its juridical approach to trade disputes based upon careful analysis of the rules benefits the weak members of the organization because a rule-based system ensures a level playing field for all.

So, if the design of the system is beneficial to LDCs, what is preventing their participation? And how can these constraints be overcome?

There are several non-WTO specific obstacles LDCs must surmount to be able to participate in the system. These include legal capacity, resource scarcity and politics.

Because of a general lack of human capacity, many LDCs face a low supply of local lawyers with expertise in WTO law. This increases the cost of advice and information on WTO matters. A WTO case is estimated to cost at least US$500,000 if taken through the Appellate Body. Small and poor members must weigh the opportunity cost of spending public money on foreign trade lawyers instead of addressing the social needs of a possibly impoverished population. Finally, many LDCs rely on preferential access to the markets of their trading partners. This might result in a reluctance to initiate trade disputes with those markets.

The lack of participation by large sections of the WTO membership, such as LDCs and African countries, means that the jurisprudence produced by the system is not influenced by their particular needs and specific characteristics. The absence of jurisprudence that addresses the concerns of weak members could eventually undermine the usefulness of the system. This would adversely affect the role of the WTO in maintaining predictability and order in multilateral trade.

The recent experience of the Philippines in the WTO dispute settlement shows how a developing country can enhance its participation in the system despite its limited resources. In the case of Philippines – Taxes on Distilled Spirits, the US and EU brought a complaint against the Philippines claiming that duties imposed on imported US and EU alcoholic drinks are discriminatory.

Lacking the internal capacity to respond properly, the Philippine government enlisted the help of government agencies in trade, finance and foreign affairs, and the domestic liquor industry, whose interest was represented by the biggest law firm in the country. The government also sought assistance from the Advisory Center on WTO Law, an international organization which provides legal assistance on WTO laws for developing countries. Although the Philippines lost the case, its experience illustrates that by pooling domestic and international resources and enlisting private sector support, a small developing country can have its day in court before the WTO.